The Spirit House: A Southeast Asian Tradition that Also Exists in the Philippines

The spirit house may be ubiquitous in Thailand and Cambodia, but the tradition exists in the Philippines as well.

Respecting the local spirits is a big deal in Southeast Asia. The spirit house is one such way spirits are given respect. If you’re driving through the streets of Cambodia or Thailand for instance, you’ll see a yard here and there lined with spirit houses, crafted and created by craftsmen, ready to be sold to anyone who has built or bought a house, or a business. It is believed that if you build a house on an empty plot of land, you must appease the spirit already living on that land by providing them a spirit house on the property1. It’s also recommended to leave offerings of garlands, food, bowls of water, candles, and even Red Fanta2.

The tradition of spirit houses can be found in many incarnations all throughout Southeast Asia, from Thailand to Laos, and into the Malay Archipelago, from Indonesia and even the Philippines.

Spirit houses aren’t as widely practiced in the Philippines, especially among the Catholic populace. The closest thing a Catholic Filipino may get to a spirit house are the tiny chapels and shrines dedicated to a local saint. Spirit houses for their original intent live on within the many indigenous communities of the archipelagic country.

This practice was recorded in Pedro Chirino’s Relacion de Islas Filipinas in 1604, where he writes:

In regard to the first point, they had no places set aside for worship, or public days for general festivities. Not until we went to Taitai did I learn that in many of the houses there was another one, but smaller, made of cane, as it were a little tower, fashioned somewhat curiously, to which they passed from the main house by a short bridge, also made of cane. In these were kept their needlework and other sorts of handicraft, by means of which they concealed the mystery of the little house. From information that I received from some of the faithful, it was in reality dedicated to the anito, although they offered no sacrifice in it, nor did it serve for other use than as it was dedicated to him--perhaps that he might rest there when on a journey, as Elias said to the other priests.

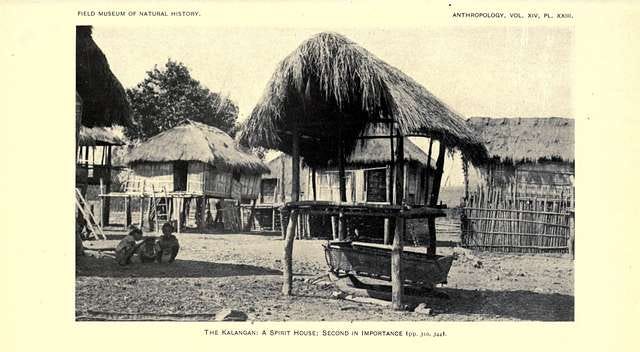

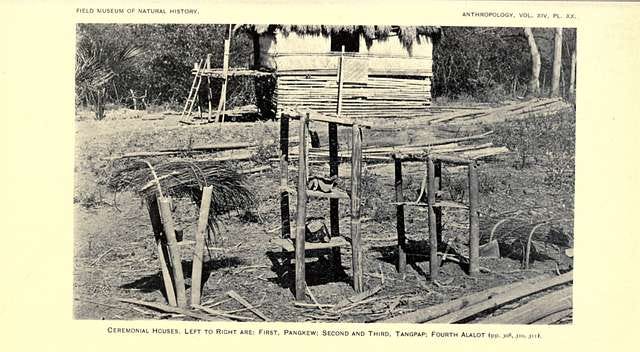

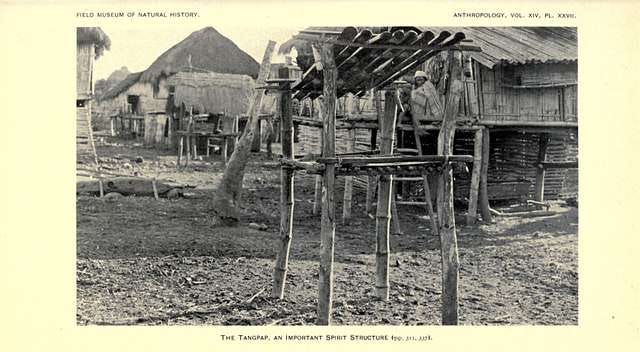

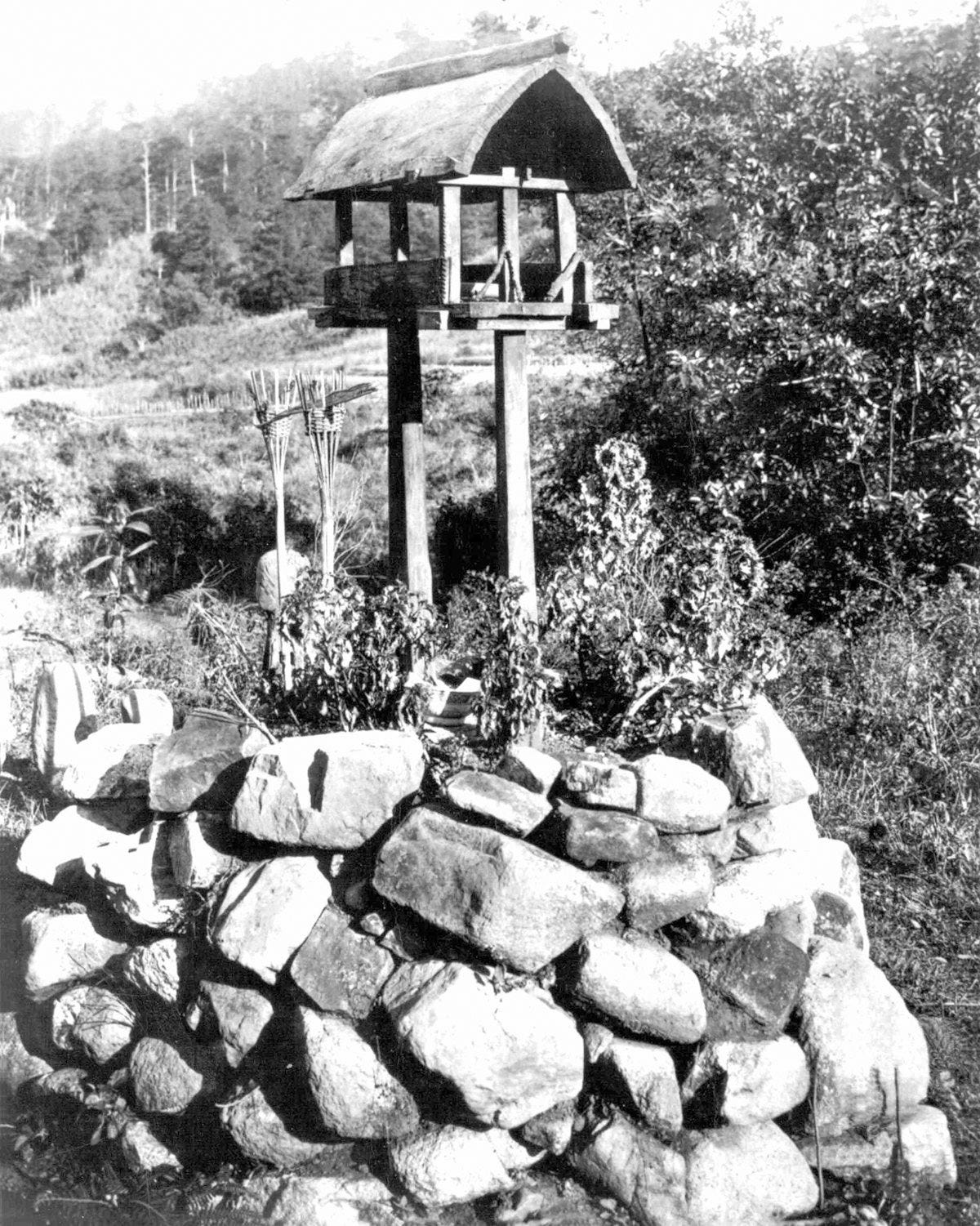

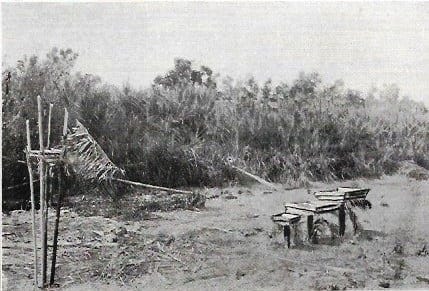

Many images of local spirit houses are from historical archives, and isn’t well documented today. Some of the most valuable images of spirit houses in the Philippines come from anthropological trips3 conducted in the early 20th century.

The Itneg people whose ancestral domains lie within Ilocos Norte have shown a tradition of spirit house building. The largest kind of spirit house was the balaua.

Similarly, the sangasang is a spirit house in the Cordilleras built solely for rituals like clan reunions or sickness. The cultures of the Kalinga and the Gaddang peoples believe that building a sangasang will appease a spirit called Bingil who could plague a village with illness.

Going further south to Mindanao, the Subanen have a recorded tradition of building spirit houses4, locally called a maligai5. Food offerings are placed in there during ritual ceremonies, with sacred dishes being placed inside the house.

Makeshift altars with offerings are often made for rituals, some of them as a form of thanksgiving to the local spirits. Alleluia Panis describes in her travels a visit6 to the Subanen people in Zamboanga del Norte and the rituals they conduct:

Placed on each of the three small offering platforms, was a plate heaped with a mound of steamed rice, three betel nut chews poking out of the rice mounds, a whole chicken, boiled with its head in tack, skin pale and bumpy, and an egg. A blue bowl held coins collected from everyone, and placed in the middle platform, while a plastic jug of cassava wine and a bowl of dark chicken blood was placed on the ground.

Timuay Mario explained the meaning of the ritual. After a series of prayers, he called on the spirits by tapping the rim of the bowl. He chanted, then took sips of cassava wine. He walked around the offering platforms several times, then he tossed the coins into the air. I watched the coins scatter, landing all over the field.

This tradition is even seen among other Lumad groups in Mindanao, including the Mandaya and the Manobo. Among the Mandaya, the building of a temporary shelter for the spirits is typically made during a thanksgiving feast, and is typically conducted after a harvest7.

After the harvest, the people hold a pyagtataan (thanksgiving) feast of bya-is (sugarcane wine), honey, and various dishes. A temporary shelter is built for a mana-ug, on which the spirit friends of harvest will descend. It stands on an altar, which is embellished with idyok leaves. Various dishes surrounding a plate of chicken liver are placed on the altar as offerings. Even the farm tools are blessed as part of the feast. The diwatahan commences with chants and prayers addressed to Kalinganan, the guardian of the fields and source of bountiful harvests, and Mananaop, protector of the fields from dangan (insects). The spirits would possess a participant, through whom they would convey their message in an unknown language. This is interpreted either by the balyan or the matikadong.

The tradition of spirit house building is present among the Manobo, where in their tradition, a babaylan conducts sacrifices and offerings are left.

Another practice similar to the spirit house is the spirit boat tradition, called by various names depending on the ethnolinguistic group. The Ibanag people call this tradition atang-atang, or ananud. A small bamboo raft containing food offerings is given to the spirit of the river, and babaylan dance around the raft to ask the spirit to accept the offering. This practice is referred to gakit by the Yogad and Gaddang, and the paanud by the Malaweg.

While most of Southeast Asia follows a form of organized religion, whether its Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, or Hinduism, Animist beliefs are still embedded in many local cultures.

Red Fanta is a popular offering in spirit houses in Thailand mainly since its color is associated with auspicious meanings.

During the American colonial period of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946, American anthropologists came to the country to study, photograph, document, and even take home artifacts and pieces of culture belonging to the indigenous peoples, from Luzon to Mindanao. It was also during this time period that indigenous Filipinos were taken from their ancestral homes and put on display in human zoo’s around America.

The Subanen also have a similar tradition called Buklog, a traditional thanksgiving ritual. Participants dance on a makeshift, elevated wooden structure, which creates a sound that is believed to be pleasing to the spirits.

In Tausug culture, maligai refers to a traditional food presentation used for special occasions, usually when children finish Quranic studies, known as pagtammat. The food presentation takes on the form of a small house.

https://alleluiapanis.wordpress.com/2010/03/08/zamboanga-subanen-tribe-ritual/

https://www.yodisphere.com/2022/09/Mandaya-Tribe-Culture-Traditions-History.html

In Ilocano culture, we set aside a small plate during parties and set it on the altar. This is called “atang,” to symbolize that the ancestors are still communing with us.

Datu Kidlat, your post on spirit houses is so enlightening! I loved how you highlighted the cultural ties in Southeast Asia, like how spirit houses, although less practiced in the Philippines, are still present in indigenous communities. "Spirit houses aren’t as widely practiced in the Philippines, especially among the Catholic populace," but your example of "the tiny chapels and shrines dedicated to a local saint" shows the intersection of traditions. It’s fascinating how, "in many of the houses...a smaller house...was dedicated to the anito." Your insights are truly eye-opening! Keep sharing this valuable knowledge, Datu! I really admire your effort here.