The Philippines and Thailand: Two Countries in ASEAN and their Cultural Similarities

Same same, but different.

It isn’t super obvious at a first glance that the Philippines and Thailand have things in common. The Philippines is a very Catholic country where the languages are written in the Roman alphabet, whereas Thailand is a very Buddhist country dotted with golden temples, writes their language using a Brahmic script, and has an overall more visible “Asian” culture to it1. Despite these differences, the two Southeast Asian countries share plenty in common, so much so that the best way to describe it would be the phrase, “same same but different”2.

A Culture of Nicknames, Polite Speech, and Hierarchy

Nicknaming Culture

A big thing that Thai and Filipino culture share is the predominance of nickname culture. How someone acquires a nickname may be completely random. Many celebrities in Thailand are known more by their nicknames than their real names, and same often goes for people. It’s not uncommon for a Thai person to use their nickname far more than their real name. Many Filipino politicians and public figures are also known by their nickname first before their real name, and nicknames are often used among friends and family. A Filipino nickname however is more likely than a Thai nickname to have some relation to someone’s real name. In both cultures, the nicknames given can be quite eccentric and quirky, and they display a good amount of flexibility.

Polite Speech and Gestures of Respect

The use of polite particles is particularly important in the national languages of both nations. In Tagalog, it’s common to use the words “po” and “opo” at the end of sentences when talking to someone older or to someone you’re not particularly close with. In Thai, the words “khap” (ครับ), or “kha” (ค่ะ) are placed at the end of sentences when the speaker is in a more formal setting, and when the person is speaking to someone older. The former is used by male speakers while the latter is used by female speakers. The usage of the Filipino and Thai words seem to largely have the same functionality and meaning. An example of how these words are used would be:

Salamat po - Thank you in Tagalog (formal)

Khob Khun Kha/Khap ขอบคุณค่ะ/ครับ - Thank you in Thai (formal)

Opo - Yes in formal Tagalog

Kha/Khap (ค่ะ/ครับ) - Yes in formal Thai

Similarly, both cultures observe gestures of respect to elders. The Philippines has pagmamano, or Mano. Thailand has the wai (ไหว้), a gesture where you clasp your hands and slightly bow. In both gestures, you bow your head slightly. Both are done towards elders or respected people in society, while in Thailand, the wai can be done to guests.

Kinship Terms In Family and Societal Contexts

Kinship terms in both Filipino and Thai culture extend to beyond actual family members. While the word “kuya” for older brother and “ate” for older sister in Tagalog are used for siblings3, they are oftentimes also used to address anyone older than the speaker who may not be directly related to them. In contexts outside of a family, using these terms shows some form of familiarity or relationship, though sometimes it can be a complete stranger. In Thai culture, the term “phii” (พี่) is used for any elder sibling regardless of gender, while “naawn” (น้อง) is used for younger siblings. These terms are also used outside of a persons family, and anyone older than the speaker can be referred to as “phii” plus their name, or just “phii” for short.

Saving Face

In both cultures, the concept of saving face and avoiding public shame or embarrassment are important facets of life. In the Philippines, this concept of saving face, also known as delicadeza, ties into the concept of hiya, or shame in Tagalog. With delicadeza, disagreements or conflicts in public settings are delivered indirectly to avoid embarrassment. Direct confrontations are taboo. Thai culture places a similar level of importance on saving face as well. Cultural norms in Thailand usually take into account ways in which to avoid losing face and avoiding confrontation. The term sia-naa (เสียหน้า) describes the idea of losing face due to public shame. This kind of culture contributes to Thailand’s reputation and nickname of the “Land of Smiles”, as smiling may be used to maintain social harmony and diffuse tense scenarios.

A Laidback, Tolerant Culture

Both Filipino and Thai culture are known for being overall relaxed and laidback. This mindset and attitude shows in how things operate in both countries. Punctuality isn’t a huge thing, as its true for the rest of the region. Both cultures can be accurately described as operating on polychronic time, or functioning in a fluid manner. For Filipinos, this is more popularly known as “Filipino time”.

Pairing with a more fluid concept of time comes the general laidback and relaxed culture that is prevalent in not only the two nations, but in Southeast Asia as a whole. While the phrase “bahala na” can mean many things depending on context and can even be quite polarizing4, it can also show how relaxed Filipino’s are when it comes to getting things done, or even the ability to get things done. In Thailand, the sabai-sabai (สบาย สบาย) attitude shows the willingness for Thai people to relax and take it easy. This even ties back to a commonly used phrase “mai pben rai” (ไม่เป็นไร)5, roughly meaning “no problem”, or another way to say go with the flow. While “bahala na” and sabai-sabai have different literal translations, the implications for going with the flow and relaxing remain the same.

Another cultural concept that is similar to the relaxed nature of bahala na is the concept of sanuk (สนุก) in Thai culture. Literally translated as “fun”, the ethos behind sanuk is that it encompasses a lighthearted approach to life, where fun is to be had at any and every moment, interspersed throughout the day, even at work6. Instead of fun being had exclusively during special occasions, sanuk is had every day, and everything from work to leisure should be enjoyable, or else its not worth engaging in.

Hospitality and a Culture of Smiling

Both countries are famously known for their hospitality and friendly nature. Its embedded in the cultures of these two countries. The culture of hospitality goes back to pre-colonial times in the Philippines as the ancient kingdoms and sultanates were important trading ports. The idea of hospitality relates to many concepts and words in the various languages of the Philippines. The concept of pagkikikapwa-tao from the Tagalog language emphasizes the importance of positive and harmonious relationships7 with others, for greater social cohesion. The word nayánayá from Visayan languages8 has various meanings, but can mean to entertain and serve others, and to be a happy person. Thailand is known around the world as the “Land of Smiles”, as smiling is a huge part of Thai culture. Smiling in Thai culture, known as yim (ยิ้ม), is a huge part of politeness and hospitality, and is seen as a way to diffuse tense situations. The concept of naam jai (น้ำใจ) similarly describes generosity as well as helpfulness and hospitality so embedded in the mannerisms.

Smiling culture in both cultures is a well-known mannerism and hugely characteristic of Filipino and Thai habits. In both countries, smiling can be done even when the person isn’t feeling happy. It is also seen as a way to diffuse situations, and reflects the need to avoid direct confrontation9. The habit of smiling is so embedded in Thai culture there are multiple versions of a smile10 that could indicate different meanings.

A Similar Sense of Humor in The Face of Disasters

One common trait that is shared by both Thai and Filipino people that could also relate back to not taking life too seriously is the ability to have a sense of humor in situations like flooding or storms. There’s a tendency to take on a lighthearted approach to these kinds of situations.

Queer Identities

Queer culture and its general acceptance in mainstream society has deep historical roots in both the Philippines and Thailand. These two countries are known for being some of the most LGBT friendly nations in Southeast Asia, with Thailand being the first country in the region to recognize same-sex marriage. Many celebrities in both countries are openly LGBT and garnered massive clout. The production of BL and GL series has made Thai pop culture famous on a worldwide scale.

In the Philippines, bakla refers to effeminate gay men or trans women, whereas laki-on or tomboy refers to women who present more masculine. In pre-colonial society, bakla performed the role of babaylan, or spiritual leader of communities. Other Filipino languages have their own words to describe bakla, such as agi in Hiligaynon, bayot in Cebuano, and binabae in Tausug. The term isn’t an exact equivalent to being gay, but moreso describes effeminate characteristics, and is often considered a natural “third gender” in local cultures. A major facet that is commonly associated with Thailand is the presence of kathoey (กะเทย), or ladyboys, which like the term bakla, can refer to trans women and even effeminate gay men. Kathoey are also seen as a third gender in Thai culture. A major difference in their respective histories is that whereas bakla were seen as spiritual leaders, some Buddhists believed that kathoey was a result from transgressions of a past life. Both bakla and kathoey still don’t have legal recognition of their identities in their respective countries and still face discrimination even with growing acceptance.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Karaoke Culture

Karaoke is one of the biggest pastimes in both countries. The Philippines is especially known for karaoke and it has garnered an international reputation for karaoke, as it’s very common to hear karaoke even late into the night. Similarly, karaoke is quite popular in Thailand, even in rural areas where it’s sometimes the only form of entertainment11. In both countries, karaoke can be done in fancy places like upscale malls, but can also be done in bars and even restaurants.

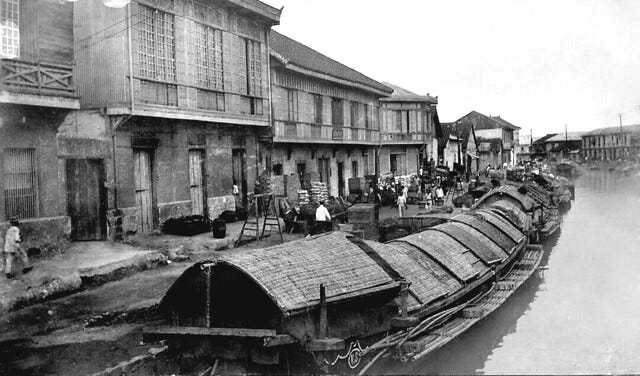

Cultures Developed on the Waterways

Rivers and coastlines are where civilizations develop, and Southeast Asia is no different. Water is especially important in the development of culture in this region. It influences the livelihoods of the people, determines how homes are built, facilitates trade, and even inspires names. The Chao Phraya River in Thailand supported the Ayutthaya Kingdom as well as the subsequent Rattanakosin dynasty in Bangkok. It was in the rivers numerous canals that Thailand developed into the society that it is today. The Pasig River gave rise to important polities like Tondo and Maynila who were part of an ancient elaborate trade network that was linked to China, Brunei12, the greater Malay Archipelago, and Malacca. The cities of Bangkok and Manila, have traditionally used canals as transportation. The canal, or khlong (คลอง), was a way of life in Bangkok, and the city is still dotted with many of them. In Manila, the esteros of the Pasig River served a similar purpose, acting as a place for trade, irrigation, and transport13. The many ethnic groups that make up the Philippines owe their names from water. Tagalog comes from taga-ilog, or “from the river”. Ilocano means “from the bay.” Maranao means “people of the lake.” Tausug means “people of the current.”

The development of stilt houses in Southeast Asia is largely due to proximity to water, as well as a response to monsoons that bring flooding to the region. This type of architecture exists in the highlands as well to protect from harsh weather. In vernacular architecture, wood, bamboo, rattan, and thatch are commonly used in both traditional Thai and Filipino houses.

Some towns and communities in both nations are even built entirely over water. Many Sama-Bajau towns in the Philippines, such as Sitangkai are built mostly over water in the Sulu Sea, and is comprised of stilt houses. Similarly, Koh Panyi in Thailand is a famous town in Phang Nga province known for being built on the waters14 off the Andaman Sea.

Shared Agricultural Practices and an Importance of Rice

Rice is Life

Wet-rice production in both Thailand and the Philippines is an especially common agricultural practice. Rice is a staple crop, and a staple food. Rice holds significant cultural connotation and is sacred. So sacred, that Thai rice farmers worship and make offerings to Mae Phosop (แม่โพสพ), a deity with ties to ancient Thai folklore. It is believed that the Rice Goddess ensures everyone has enough rice to eat. Her shrines and images are often found in the rice fields. Similarly, the Igorot peoples in the highlands of the Philippine Cordilleras believe the bulul watches over the rice terraces, ensuring a good harvest and protection from pests. Statues of bulul watch over the rice terraces, and are effigies of the ancestors and guardian spirits.

Rice is also celebrated in both countries. The Royal Ploughing Ceremony in Thailand marks the start of the rice-planting season. Two sacred oxen plow a field and its believed to predict the agricultural yield for the year. Rice festivals are celebrated throughout the Philippines. In the province of Quezon, Pahiyas festival celebrates the harvest, and uses a local form of folk art made of kiping, a leaf-shaped wafer made from rice. The punnuk tradition, a local tug-of-war of the Ifugao people marks the end of the harvest season and the beginning of a new one.

Traditional forms of dress are even tied to agricultural practice. The Asian conical hat is one such example. The ngob (งอบ) is also known as a Thai farmer’s hat. The salakot in the Philippines, while having royal connotations in the past, is commonly associated with farmers and agrarian practices. The shape of the ngob differs from the salakot and most other variations of the conical hat in that it has a flat top, and is primarily made from ola palm leaves laid over a plated bamboo-strip frame.

The importance of the water buffalo is also prevalent. For rural Filipinos and Thais alike, the water buffalo plays an important role in rice farming. Water buffalo are often celebrated in both cultures, with festivals highlighting the importance of the animal in agrarian communities. Carabao in the Philippines are a different species of water buffalo from the Siamese buffalo found in Thailand.

Traditional Healing and Massage Traditions

An interesting facet that both countries share is the existence of traditional massage practices. These massage traditions tie into traditional medicine, as these practices are seen as a way to heal. Hilot is a traditional massaging practice in the Philippines that aims to promote balance. Pressure is applied to muscles and joints to promote body healing. A manghihilot performs this procedure, and this line of work is often passed down through the generations. They often provide a lower cost for their services when compared to modern medicine. The use of hilot ties into the traditional practices of ensuring the total well-being of a person15. Similarly, Thai massage, or Nuat Thai (นวดไทย), also uses acupressure. Thai massage combines Ayurvedic principles and assisted yoga, and unlike manghihilot practitioners, can be found and offered in mainstream religious institutions16. Similar to hilot, Thai massage aims to reduce tension and ease symptoms17. A major difference between the two massage traditions is that many hilot practices are passed down between families who practice hilot and thus are heavily localized whereas Thai massage has a set standard as a result of institutional practices, and is mass promoted by the Thai government as an aspect of Thai culture and heritage.

Traditional medicine and healing practices are still widely practiced in both countries. Seeing an albularyo in the Philippines is still a common practice in many rural communities where modern medicine is hard to come by. An albularyo, similar to a manghihilot, uses traditional herbs and medicinal practices to heal a patient18, and there is usually a spiritual element in these sessions. Albularyos use pagtatawas to diagnose a person of an ailment or a disorder. In Thailand, traditional Thai medicine is an institution and have five main primary branches that take inspiration from Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic principles, and indigenous methods. Mor Baan were traditional practitioners of traditional medicine19 in Thailand before the introduction of Western medicine. Similarly, both traditional Filipino and Thai medicinal practices adhere to the balance of four elements (earth, fire, water, wind), and the use of these medicines are meant to heal and restore a balance with all of these elements.

Respect the Spirits, Or Else…

While the major religions seemingly reign supreme in Southeast Asia, the reverence of local spirits holds more preeminence over the teachings of the Buddha, Brahmin, Christ, or Allah. Those local spirits that live right at the doorstep are believed to be just as deserving of respect as any being. This belief manifests in many ways throughout Southeast Asia, with the most common physical representation of this reverence being the spirit house. In Thailand, the spirit house is as ubiquitous as a 7-11 or a temple. Any corner of Thailand, a spirit house is there. Usually when a new building is constructed, a spirit house is erected right beside it to serve as the new home of the local spirit. The tradition of spirit houses in the Philippines is relegated to indigenous peoples.

Another important aspect of spirituality is the banyan tree, where in the Philippines it’s locally referred to as the balete tree. The banyan tree is considered to be sacred and home to protective spirits, and should never be tampered with, its multiple roots allowed to fan out in all directions. In Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha Gautama sheltered under the tree.

The Influence of India

Indianization came in waves over the centuries in Southeast Asia. While it’s most obvious in Thailand, the influence of Indian traditional religions and practices has made its way to the Philippines. Where Thailand has adopted Theravada Buddhism and is promoted in the Thai constitution, societies in the Philippines remained largely Animist in pre-colonial times, with various kingdoms and communities picking and choosing various Hindu and Buddhist traditions to adopt20. One of these instances was the adoption of the belief in the naga, which was syncretized with the Visayan bakunawa. Naga dragons flank the reliefs and staircases of many Buddhist temples throughout Thailand, whereas visual representations in traditional art in many cultures of the Philippines are relegated to sword hilts in Visayan cultures, as panolong in traditional Maranao homes, or on prows of Sama-Bajau boats. Furthermore, the Phaya Naga (พญานาค) in Thailand takes on a more significant aspect of Thai culture as its considered a national symbol of Thailand, and constantly show up in stories, artwork, and theater.

Another example is the Ramayana, a Hindu epic that narrates the life of Rama. The Ramakien (รามเกียรติ์), the Thai version, is considered to be the national epic of Thailand. The Ramakien is referenced in many khon drama, regional dance troupes, as well as in traditional literature. In the Philippines, the Ramayana is confined to the Maranao people in Mindanao, as they have a local version known as Maharadia Lawana that takes on a localized form. Unlike Thailand, many Filipino societies have received secondhand Indian influence, so the Maranao version of the Ramayana has influence from Javanese and Malay versions.

Additionally, the use of white jasmine, which originates in the Caucasus and South Asia, has spread to Southeast Asia and has taken on some religious and spiritual connotations. White jasmine, known as dok ma-li (ดอกมะลิ) in Thai and sampaguita in Tagalog, is used as offerings as well as decorations. In Thailand, the use of white jasmine is popular in phuang malai (พวงมาลัย), or floral garlands used for offerings in temples. In the Philippines, the sampaguita is considered to be the national flower, and like the use of white jasmine in Thailand can also be used in religious offerings, particularly in the veneration of saints.

Artistic Expressions

Percussion Ensembles

The tradition of gong-chime and percussion ensembles is a common musical tradition found in much of Southeast Asia. Kulintang ensembles found in Mindanao typically include the kulintang as well as hanging single brass gongs and drums. Piphat (วงปี่พาทย์) is a local percussion ensemble in Thailand that normally makes more use of xylophone-like instruments rather than gongs. One of the xylophones in a piphat emsemble, the ranad (ระนาด) instrument, much like the Filipino gabbang, is made of bamboo. Khong wong yai (ฆ้องวงใหญ่) are the only gongs used in a xylophone and chime dominated piphat ensemble, and are arranged in a circle whereas kulintang is arranged in a straight line.

Long Fingernail Dances

Some regional dances include wearing long fingernails and elegant movements. Pangalay is one of those elaborate dances rooted in Tausug and Sama tradition in the southern Philippines, where elongated fingernails, or janggay, are worn by dancers. Menora (มโนราห์) in southern Thailand also uses similarly long metal fingernails, where dancers tell tales of the Buddha and of ancestral wisdom. Both dance traditions feature graceful movements and outstretching of the arms, as well as the use of gongs and drums that include fast-paced rhythms while hand movements are often slow. Whereas pangalay fingernails are often straight, menora fingernails are curved toward the dancer. Both traditions often use improvisation with live music.

Folk Dances

In the realm of folk dances, both Thailand and the Philippines share quite a few in common. Certain props can be seen in folk dances practiced in both countries.

Coconut shells in dance is one such prop. Maglalatik in the Philippines depicts a mock battle for coconuts, with shells attached to dancers. Serng Krapo in the Isan region of Thailand also uses the shell of the coconut, though it differs in that the shells are only held by dancers rather than worn.

There are also many folk dances in both countries that employ the use of fans. Both the Pagapir dance of the Maranao in the southern Philippines and the Rabum Tarikipas in southern Thailand21 comes from Muslim groups in the respective nations. Pagapir was primarily danced by ladies of royal Maranao courts. Graceful and demure movements are present in both dances, whereas Rabum Tarikipas was performed along coastal fishing villages.

Another similar folk dance involves the use of balancing candles or lamps. In the Philippines, Pandanggo sa Ilaw from Mindoro features dancers swaying to rondalla music whilst holding and balancing lamps. Fon Tian in northern Thailand has dancers perform with candles in their hands while performing flexible movements.

Weapons-Based Martial Arts

The tradition of weapons-based martial arts runs deep in the histories of both countries. In the Philippines, Kali, or Arnis, is considered a national sport. While the most famous depiction of the martial art uses sticks, it also uses weapons. Krabi-krabong (กระบี่กระบอง) in Thailand emerged as a need for battlefield combat, as ancient Thai kingdoms fought with neighboring kingdoms like the Burmese and Khmer. The use of bladed weapons and poles is similar in both forms of martial arts, though footwork and techniques differ greatly.

Culinary Traditions and Cooking Techniques

It may not seem like it at first, but Filipino and Thai food traditions share quite a bit in common. The cuisine between the two countries is where the phrase “same same, but different” really comes along. Ingredients such as rice, coconut milk, lemongrass, fish sauce, shrimp paste, mangoes, banana leaf, a plethora of tropical fruits and vegetables both native and non-native, tamarind, chilis, and noodles are abundantly used in local cuisines, playing very similar, but also different roles at times.

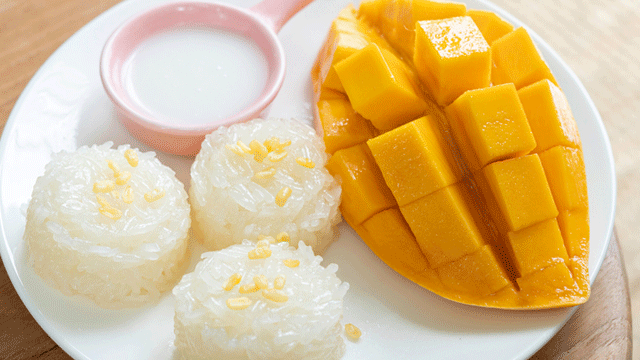

The Perfect Pair

Mango sticky rice (ข้าวเหนียวมะม่วง) is probably the most famous dessert in all of Thailand. It’s a great pair: sweet mangoes and glutinous sticky rice, along with some toasted sesame seeds, all topped with coconut milk. Similarly, a dish called puto maya from the Visayans in the central Philippines utilizes this sweet mango and glutinous sticky rice, or malagkit, pairing. A difference between the two is puto maya is eaten in a breakfast setting with a side of sikwate, or local hot chocolate which could also be poured on top, whereas Thai mango sticky rice is seen as a dessert.

Stir-Fry Noodles among other Chinese Migrant Dishes

The national dish of Thailand, pad thai (ผัดไทย), may have been invented by the Thai government22, but the tradition of stir-fry noodles in a wok, or krata (กระทะ), goes back to Chinese migrants into the kingdom. Thailand has many other noodles dishes and are collectively referred to as kwai tiao (ก๋วยเตี๋ยว)23. Similarly, many noodles dishes in the Philippines which are collectively known as pancit24 are also stir-fried in a kawali, a local version of a wok. Rice noodle dishes from Thailand include pad thai, pad see ew, and khao soi, and in the Philippines includes pancit bihon, pancit palabok, and pancit Malabon among others.

Other examples of noodle dishes from Chinese influence include wonton noodle dishes. Wanton mee (บะหมี่เกี๊ยว) in Thailand is served with egg noodles, wontons and barbeque pork. In the Philippines, pancit Molo from Iloilo is one of the local wanton noodles, and is unique in that it uses the wanton wrappers as noodles.

The influence of China extends to more than just noodles. Chinese migration into Southeast Asia has had long-lasting cultural and demographic change. Thailand has the largest Chinese diaspora in the world. The Philippines also has a pretty influential and significant Chinese diaspora community, many of whom run famous businesses. Many street foods in both Thailand and the Philippines come from Chinese migrants25, many of these are widely known.

Chinese-style baozi (包子), or steamed buns, also take on localized forms. Siopao26 is a popular Filipino street food, and is pretty similar to its Thai counterpart, salapao (ซาลาเปา). Both versions come from migrants hailing from southern China, and they don’t differ that much from each other as they tend to have similar popular fillings like salted egg and barbeque pork27.

Fried dough, or youtiao (燒餅) is also another street food that came from Chinese immigrants. Bicho-bicho refers to the fried dough in Filipino street food. In Thailand, pattongo (ปาท่องโก๋) can be eaten as a breakfast or alongside porridge. A major difference between the two versions is that bicho-bicho is oftentimes coated in sugar or caramel syrup, whereas pattongo can be dipped in pandan or in coconut milk.

Soy sauce as a condiment is also popular in both Filipino and Thai cuisine, a result of Chinese migration. It is used in stir fries as well as in noodle dishes, and in dipping sauces.

A popular breakfast item from Chinese influence is rice porridge, or zhou (粥) in Mandarin. In the Philippines, it is generally called lugaw, whereas in Thailand it’s called jok (โจ๊ก), usually served with minced pork and chopped spring onions.

Steamed dumplings are also a popular street food in both countries. Siomai in the Philippines is unique in that it can be eaten with a stick with a side of calamansi. In Thailand, khanom jeeb (ขนมจีบ) is made from ground pork and prawns.

Spring rolls are another example of Chinese influence. They are called lumpia in the Philippines, and popiah in Thailand. Both examples use wrappers made of rice flour, and are often fried. A main difference is lumpia has a bigger presence in the perception of Filipino cuisine compared to Thai cuisine.

The use of specific vegetables in local cuisines also come from Chinese migration, including Chinese cabbage, mung bean sprouts, and Chinese mustard greens.

Mooncakes are also localized in both countries. In the Philippines, hopia refers to a flaky pastry usually with red bean filling, though ube is also a popular filling. Mooncakes (ขนมไหว้พระจันทร์) in Thailand are usually sold during Mid-Autumn Festival, with lotus seed filling and egg yolk as popular fillings. Khanom pia (ขนมเปี๊ยะ) is another Chinese-inspired pastry with a similarly flaky crust with either a savory or a sweet filling.

Shrimp Paste

Shrimp paste is one of those essential Southeast Asian ingredients, to the point where communities rely on shrimp paste consumption and production to fuel economies. Locally known as krapi (กะปิ) in Thailand and bagoong in the Philippines, shrimp paste is used in many dishes, especially in dips and sauces. Many Thai spicy sauces called nam phrik (น้ำพริก) use shrimp paste. A difference between the shrimp paste between the two countries is that in the Philippines, during the process of making bagoong alamang, the shrimp is still identifiable whereas most shrimp paste production in most of Southeast Asia grounds the shrimp until it’s unrecognizable. There is also a cooking method in the Philippines called binagoongan, which specifically refers to any dishes that use bagoong alamang in cooking.

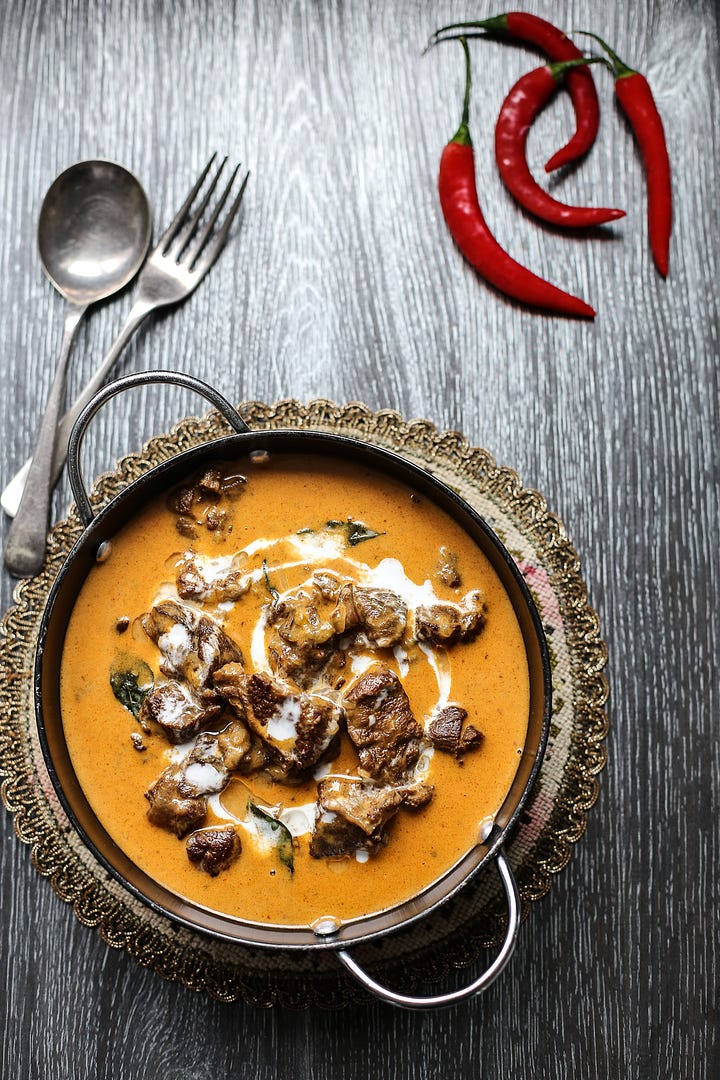

Curries and Spice

While Thai cuisine is famous for its use of curries and being one of the spiciest cuisines in the world, there are a few regions in the Philippines that are locally known for liberal use of chilis and the existence of curry dishes. The regions of Bicol and Bangsamoro in the Philippines are known for being spicy in a country where milder flavors, and sweet and sour profiles dominate local palettes, and where chilis are largely relegated to condiments. Palapa refers to a local ingredient in Maranao cuisine that is popular in many local dishes, and uses a lot of chilis. Local curries in Thailand collectively known as kaeng (แกง) include kaeng pa, Massaman curry, Phanang curry, and phat phrik khing, whereas some local curries in the Philippines include local chicken curry, and kulma, linigil and tiyula itum from the Bangsamoro regions.

The Use of Tamarind

The sour notes in tamarind adds flavor to many local dishes. In the Philippines, tamarind, known locally as sampaloc in Tagalog, is a key ingredient in sinigang, a popular sour soup. Tamarind, known as makaam (มะขาม) in Thai, gives a sour note to tom yum (ต้มยำ), a general term for a type of hot and sour soups, though lime juice is the common source of acidity. Another soup called tom khlong (ต้มโคล้ง) uses tamarind as a main source for a sour flavor.

The Versatility of Coconut Milk

Coconut milk in cooking ranges from savory and spicy foods to desserts and drinks. It is probably the quintessential ingredient in the general culinary traditions of Southeast Asia. Coconut naturally grows in the region, and is so abundant, so coconut and any coconut-based products are a huge aspect of local cuisine. In the Philippines, ginataan is a cooking method that describes any dish that is cooked in coconut milk. Dishes such as ginataang ampalaya, ginataang kalabasa, laing, and piaparan are some of the main dishes that fall under this category. One similar dish both countries have is unripe jackfruit with a savory flavor cooked in coconut milk, known as ginataang langka in the Philippines and kaeng khanun in Thailand. Many Thai curries make use of coconut milk, as well as soups and desserts.

One particular dessert in both countries is a coconut-milk based dessert soup with glutinous rice balls, known as ginataang bilo-bilo in the Philippines and bua loi (บัวลอย) in Thailand, though the Filipino counterpart may include pieces of jackfruit and sago. Other desserts that use coconut milk heavily include ginataang mais, binignit, and ginataang munggo in Filipino cuisine, and khanom tuay and kluai buat chi in Thai culinary traditions.

Another dessert uses bananas cooked in coconut milk. Bananas are another popular ingredient in many desserts, one example being ginataang saba in the Philippines. The Thai counterpart of this dish is called kluai buat chi (กล้วยบวชชี), and is also enjoyed in neighboring Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Malaysia.

Pork, Roasted and Barbequed

Pork dishes are common in both cuisines. The tradition of whole roasted pork for instance, is one culinary tradition shared in both countries, though its more commonly associated with the Philippines. The tradition of lechon, a name acquired from Spanish but the cooking method Austronesian, can also go by the native name inasal na baboy, and is widely associated with festivals. Similarly, the tradition of moo han (หมูหัน), or whole roasted pig is practiced in Thailand.

Braised pork dishes are another example of shared culinary heritage. Originally brought by Hokkien settlers, braised pork belly goes by different names, humba in the Visayas region of the Philippines and moo hong (หมูฮ้อง) in southern Thailand. One difference is the use of fermented black beans in humba, and the use of coconut sugar in the Thai version.

Char siu (叉燒), or Cantonese-style barbeque pork, is also present in both countries food traditions. In Thailand, char siu, known locally as mu daeng (หมูแดง) is found in many noodle dishes and eaten alongside rice. Barbequed pork in the Philippines known as Chinese pork asado can be eaten with cold cuts or served as filling in siopao.

Crispy pork rinds are also eaten in both nations. In the Philippines, chicharron is typically eaten as a snack or as pulutan, dishes eaten with beer. The dish khaep mu (แคบหมู), a specialty of the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai can be eaten as a starter meal. Both versions are prepared the same way.

Drinking Food

Drinking culture is a big part of the local culture in the two countries. Both countries have their own famous local beer brands, and at bars and other drinking establishments, there are foods commonly associated with drinking culture. In the Philippines, inuman is generally used to describe a drinking session and pulutan refers to any snack or meal served alongside alcoholic drinks. The most popular pulutan include sisig, crispy pata, lechon kawali, and tokwa’t baboy. Thai drinking culture is referred to as kap klaem (บแกล้ม), whereas ahan kap klaem (อาหารกับแกล้ม) is the Thai term for foods commonly eaten while drinking. Certain examples of ahan kap klaem include phat khimao, drunken noodles, and laap muu thawt or pork salad. In both cultures, these foods are often heavy and appeal to the working class, and oftentimes are fried and have a smoky flavor.

A Miscellaneous Assortment of Street Food and Snacks

A major aspect of life in both countries is the proliferation of street food from morning until late into the night. Street food culture is a huge part of the local culture, from popular streets to night markets, and can either be full meals or just eaten as a light snack. Many of the dishes mentioned above are already popular street food items but there are a few more worth mentioning which both countries share.

Satay (สะเต๊ะ) and other forms of barbeque skewers are one such street food that is popular in both Thai and Filipino street scenes. Isaw in the Philippines, or chicken intestines, is similar in that the cooking method involved grilling the skewers over an open fire. There is even a local version of satay known as satti, a Tausug delicacy served with a spicy sauce and popular in the southern Philippines. A major difference between satti and satay is that satay in Thailand is served with a side of peanut sauce. A pork option for this dish exists in both countries, one of the ways it differs from Indonesia, where satay has its origins. Additionally, satay is most commonly associated with Thai food in much of the Western world, despite its ubiquity in Southeast Asia.

Fish balls are another popular street food option. They’re most commonly found in the Philippines in the tusok-tusok style, eaten by poking it with a stick and dipping it in a sauce. In Thailand, fish balls known locally as luk chin blaa (ลูกชิ้นปลา) can be eaten in a similar way, but can also be in noodle soups and in curry dishes.

Fried banana comes in many forms, especially in Southeast Asian countries where the fruit grows naturally. Fried banana as a snack can exist as a dessert lumpia known as turon or as a skewered form known as banana cue. A similar dish in Thailand is known as gluay kaeg (กล้วยแขก). Banana fritters are another common dish, locally known as maruya in the Philippines and gluay tod (กล้วยทอด) in Thailand. Both these variations use plantains but the Filipino counterparts may also use saba bananas.

The way ice cream is consumed also reflects the vibrant street food scene that exists between the two countries. Local ice cream commonly sold in a colorful pushcart is called sorbetes in the Philippines, and is unique in the use of coconut milk or carabao milk. They come in unique flavors like queso, avocado, buko, or ube, and some sorbeteros would serve the ice cream in pan de sal to make a bread ice cream sandwich. A unique way to create ice cream was invented in Thailand called stir-fried ice cream (ไอติมผัด), or rolled ice cream in the global scene. This popular street food has since spread to other countries, and is made with a milk base that is combined with other fresh ingredients and syrups to create flavor.

Glutinous sticky rice cooked in bamboo tubes is a unique cooking tradition that both countries share. Usually associated with Christmas season, puto bumbong is made with a native purple sticky rice called pirurutong in Tagalog, or tapol in Visayan, and cooked in a bamboo tube. The snack is traditionally eaten outside of churches in stalls for Simbang Gabi practitioners. It is one of the quintessential Filipino Christmas street foods, alongside bibingka. Similarly, khao lam (Thai: ข้าวหลาม: Lao: ເຂົ້າຫລາມ) is popularly sold in the streets of Thailand and Laos, may also use white or dark purple varieties of glutinous rice locally called khao niao dam (ข้าวเหนียวดำ) though it may also be cooked with red beans and custard inside. Khao lam has another similarly religious connotation in that Thai Buddhists use the dish to present to monks in order to make merit.

Sweet crepes made with rice cakes are a snack and can be a common street food. The Tausug dish daral refers to a dessert crepe rolled into a cylinder and filled with hinti, a sweetened coconut meat. This dish has its equivalent nearby where goes by many names like kuih dadar and dadar gulung in Indonesia and kuih gulung in Malaysia and Brunei. Originally made during the Ayutthaya Period, khanom bueang (ขนมเบื้อง) is a Thai style crepe that like Tausug daral can also be filled with shredded coconut. Some major differences between the two dishes is that khanom bueang has a crispy texture, can have Foi Thong filling, or be savory, whereas daral, like its counterpart in neighboring countries, is primarily sweet and softer in texture.

Cold pandan dishes that can sometimes be drinks are another popular snack. The traditional Filipino dessert buko pandan salad is a cold dessert soup with gulaman, shredded coconut, tapioca, and other jellies. The dish lod chong (ลอดช่อง) in Thailand uses similar ingredients and has a similarly green color, but can also include shaved ice. Both desserts share similarities to cendol, a dish of shaved ice and jelly-like toppings which is widely eaten in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei.

Shaved ice desserts with toppings, another classic Southeast Asian dessert, has its own local varieties. The most famous one in the Philippines is halo-halo, where shaved ice is topped with nata de coco, mixed jellies, coconut milk, and ice cream. Similarly, namkhaeng sai (น้ำแข็งใส) refers to shaved ice with sweet syrup and condensed milk, with an additional amount of toppings referred to as namkhaeng sai ruan mit (น้ำแข็งใสรวมมิตร). These toppings28, like in halo-halo may also be fruits, coconut jellies, or sweet corn but may also include chestnuts and candied taro.

Rice cakes also come in many forms, and they make up a huge part of the dessert and street food scene. In general, kakanin refers to all the rice cakes or rice-cake adjacent dishes29 in the Philippines typically made of coconut milk and malagkit, the local word for sticky rice. Rice cakes like puto, bibingka, kutsinta, suman, and biko are often the most famous examples of kakanin in the country. Any form of sweet or dessert typically falls under the term khanom (ขนม) in Thailand, and the many rice cakes that are traditionally eaten fall under this category. The local word for sticky rice is khao niao30 (Thai: ข้าวเหนียว: Lao: ເຂົ້າໜຽວ) in Thai.

For some further examples, Khanom tan (ขนมตาล) and khanom tai fu (ขนมถ้วยฟู) bear similarities to puto, as they are steamed rice cakes made with coconut milk. Khanom tan differs from puto in the use of toddy palm, and khanom tai fu31 is considered one of the nine auspicious Thai desserts due to its name. Khao tom (Thai: ข้าวต้ม; Lao: ເຂົ້າຕົ້ມ), popular in Thailand and Laos, refers to a dessert made of sticky rice, ripe banana, and coconut milk wrapped in a banana leaf, similar to the way suman in the Philippines is prepared, where malagkit is wrapped in a banana leaf and elongated. Khanom chan (ขนมชั้น), a layered cake made from tapioca and rice flour, which originated in the Sukhothai Period, has a similar appearance to sapin-sapin, a local Filipino version of a layered cake also made from rice flour.

Facets of Urban Life

Megacities

A common feature in Asia as a whole is the existence of megacities. Both the Philippines and Thailand have their own megacities, which are also the capitol cities of their respective nations. Bangkok and Manila are the largest cities in their nations, with the Bangkok metropolitan area being home to around 17 million people and the Manila metropolitan region home to over 14 million people. These are the wealthiest parts of both countries, as well as where much of the political, economic, cultural, and social power lies. Bangkok is an example of a primate city, where the city is disproportionally larger in population than to the next largest city in the country. This further perpetuates Central Thai culture and Central Thai language as the standard for how Thai culture is perceived. Similarly, the Tagalog language is pushed nationwide in the Philippines, and is taught on a national level.

Modes of Transport

Bangkok and Manila are known for their traffic, and in general, cities are known for the abundance of motorbikes, as well as the use of Grab, a popular ride-hailing app. The major cities, even though the national capitols have their respective metro and rail lines, are still heavily car-centric, though personal motorbikes are very common.

In the cityscapes of both countries, the auto-rickshaw is a common sight. The tuk-tuk (ตุ๊ก ๆ) is ubiquitous in Thai cities, and is commonly associated with urban transport. The tricycle in the Philippines is a similar mode of transport that has a similar level of ubiquity in Filipino cities. A major difference is the sidecar for a tricycle is often on the side of a motorbike whereas the passengers in a tuk-tuk are seated behind the driver of the rickshaw.

Vehicles like pickup trucks and jeeps have been adapted to local needs, where extensions have been added to accommodate passengers. The jeepney is one of the most famous of Filipino transport, as their widely known for their loud art and maximalist designs. Similarly, the songthaew (สองแถว) seen in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar was adapted from a pickup truck and acts like a bus. Both modes of transport evolved from a share taxi of earlier periods. They even have the same seating arrangement where the seats are on the side of the vehicle. Jeepneys tend to be more flamboyant in design as opposed to the minimal songthaew.

Mall Life

Another feature of urban life in Filipino and Thai cities is the huge mall culture. Malls in the big cities are popular hangout spots, and are often big tourist draws. Places such as SM Mall of Asia in Manila and Iconsiam in Bangkok are renowned for their sheer size as well as shopping options.

Islam and the Influence of the Malay World

An interesting feature that may be coincidental is the status of Islam. It is the second largest religion in both Thailand and the Philippines, it makes up a majority of the population in the southernmost regions, and these respective regions have centuries of deep Malay influence. In fact, three of the southernmost provinces in Thailand are majority Thai Malay in ethnic background, whereas the Bangsamoro region in the Philippines are made of of various Moro ethnic groups like the Maranao, Maguindanao, Tausug, and Sama-Bajau. The southernmost provinces of Thailand have historically been home to Malay people, so therefore the provinces of Satun, Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat are majority Muslim. A coincidental demographic fact is that, Islam constitutes around 6% of both Thailand and the Philippines.

Islam arrived in that part of Thailand in the 9th century whereas the Philippines received Islam in the 13th century. The influence of Malay sultanates proliferated the spread of Islam in the area. The Sultanate of Pattani and the Sultanate of Sulu and Maguindanao had close ties with the sultanates in Malaysia, and thus absorbed a lot of that religious and political influence.

Given the proximity to Malaysia, the traditional style of dress found in the Malay Peninsula has spread to the local population in southern Thailand and the southern Philippines. The songkok, baju melayu, and sarong are the basic traditional outfits in these regions. This also extends to blading traditions like the kris sword as well as traditional Malay homes. Traditional mosque architecture in the area was also made of native materials and was built in a pagoda-like design, with pagoda like roofs.

A huge aspect of what would be considered visible “Asian” culture in this case would be the presence of Buddhism and other Dharmic religions. From a Western perspective, Thailand has the more clearly visible culture that is typically categorized as Asian.

The phrase comes from a Thai-English saying that foreigners often hear in Thailand from Thai people in an attempt to sell things, but can also be used to summarize subtle differences in a general sense.

Other Filipino languages use similar phrases to describe elder siblings. In Kapampangan, '“koya” and “achi” describe older brother and older sister, respectfully.

Some critics of the “bahala na” mindset view this mentality as fatalistic and enabling laziness. They even go far as to saying this mindset is holding the country back from progress or any real change.

Another way to look at the usage of “mai bpen rai” could go back to Buddhist beliefs. How someone’s attitude and actions are in life can dictate what their next life may be.

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20151119-can-thailand-teach-us-all-to-have-more-fun

https://jefmenguin.com/pakikipagkapwa-tao/

https://www.bbc.com/storyworks/travel/specials/a-considered-holiday/the-friendliest-people-in-the-world/#:~:text=So%20that%20is%20something%20that,together%20to%20help%20each

https://vogue.ph/beauty/wellness/behind-our-smile/

https://www.theluxurysignature.com/2024/11/27/the-power-of-a-smile-how-thailands-culture-speaks-through-this-simple-expression/#:~:text=The%20Thai%20smile%20is%20more,make%20someone%20feel%20at%20home.

https://www.thailandblog.nl/en/achtergrond/karaoke-thailand/

Members of Tondo and Manila royalty intermarried with the royal family in Brunei. Raja Ache of Maynila married a princess of Brunei.

The importance of these waterways have diminished in recent times. Many khlong in Bangkok have been filled over and some of the esteros in Manila, once places of commerce and even places of recreation have been associated with urban poverty and grime. Current projects in Manila include cleaning up the esteros and the Pasig River and making them places of commercial activity.

An interesting similarity that Sitangkai and Koh Panyi have is that these towns are majority Muslim. Ethnic Sama people in Sitangkai are one of the Moro peoples in the Philippines. Koh Panyi was founded by Javanese fishermen.

https://vogue.ph/beauty/wellness/traditional-philippine-hilot-everything-to-know/

Wat Pho, one of Bangkok’s most famous and culturally significant temples, has been the center for the development of Thai massage for centuries.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4587431/ This study shows that Thai massage may help reduce the intensity of chronic headaches.

https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/albularyo-origins-and-practices-philippines-a00293-20200418-lfrm?s=1p35m5c842i3br761q7uq58eas Herbal knowledge of albularyo has a wide range, to the point where the DOST has granted existing albularyos as alternative healthcare providers.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-011-9360-z

Some evidence of Hindu Buddhist influence in the Philippines are the gold artifacts from the 10th to 13th century found in the country, including kinnari statues, the Golden Tara, some garuda motifs and other examples of Hindu symbolism.

https://www.somapadance.org/video

The dish pad thai was invented in the 1930s by the Thai government as a way to galvanize nationalism during a time of nation-building.

The term kway tiao comes from the Hokkien word kóe-tiâu (粿條), a flat rice noodle.

The term pancit comes from the Hokkien word pán-si̍t (扁食), flat or thin food.

In Bangkok, Yaowarat Road in Chinatown is one of the most popular spots in the city for street food. In Manila, Binondo, or Chinatown is also known for its street food culture with massive Chinese influence.

The term siopao comes from the Hokkien word sio-pau (燒包).

Barbeque pork in Filipino siopao takes on a Spanish term ‘asado’, or siopao asado. The use of Spanish terms to describe Chinese or native dishes in the Philippines was intended to give these dishes legitimacy to the upper class.

https://www.eatingthaifood.com/restaurants/impressive-nam-kang-sai-at-udom-suk-thai-shaved-ice/

Cakes made from root vegetables like cassava and taro may also fall under this term.

Sticky rice is especially important in Laos and Thailand. Laos has the highest consumption of sticky rice per capita in the world, and the Isan region in Thailand is ethnically majority Lao.

Another name for this cake comes from the Hakka fa gao (發糕), and is consumed on Chinese New Year and meant to bring wealth.

This was intriguing and I saw many overlaps with Indian culture, especially the concept of saving face. I wonder if the word 'hiya' comes from the Urdu word 'haya' with the same meaning. I didn't know there were so many similarities in the Thai and Philippino culture. Thank you for sharing the lovely pictures too. They added to the beauty of this post.

Finally had the opportunity to read this article from front to back, start to finish. Very nice with the delicadeza comparison, and another nice one for the bahala na mention. You really tried your best to find as many analogous connections as possible. Brilliant read!