The Philippines and Indonesia: Two Sibling Nations and their Cultural Similarities

Centuries of colonial rule under separate Western empires has not severed the cultural ties and similarities between two of the largest archipelagic nations in Southeast Asia.

Two modern maritime Southeast Asian nations sit within the Malay archipelago1, a string of islands when combined amongst the two, make up around 24,000 or so islands2, plus a combined population of almost 380 million people3, are free sovereign states that are like twins separated at birth. Centuries of European colonial rule disrupted a millennia of trade, commerce, and cultural exchange, only for that exchange to bounce back post-independence. When looking at the Philippines and Indonesia, surface-level impressions and stereotypes of the two nations' respective cultures show a heap of differences, but despite all of that, the two countries share so much in common from a cultural standpoint that is worth noting.

Respect for Elders, A Culture of Sharing and Community, and A Need For Social Harmony

The social culture of both the Philippines and Indonesia can best be described as collectivist; family and community-oriented with a greater emphasis on the overall well-being of a group versus that of an individual, and hierarchical; a deference to elders and those of higher status through means of polite speech as well as the use of specific gestures to defer respect.

This manifests in different ways.

A Culture of Community and Mutual Aid

The idea of community cooperation shows up in the form of Bayanihan spirit in the Philippines and a similar concept of Gotong-royong in Indonesia, particularly among the Javanese people. Both concepts refer to mutual aid, where the community comes together to help one another. These concepts are a core aspect of the cultures of their respective nations. Interestingly enough, the visual representation of bayanihan, where the community comes together to physically move a house from its foundations, has a similar practice on the island of Sulawesi called Mappalette Bola, practiced by the local Bugis people.

A Shared Culture of Gift-Giving

Gift-giving, especially in the context of gifting souvenirs, is a pretty large part of Asian societies, and the Philippines and Indonesia are no different. In fact, souvenir culture is a huge part of the tourism industry in their respective nations. Pasalubong in the Philippines is given to family and friends after someone comes home from a trip, and is often unwrapped. The pasalubong given is usually representative of the place they visited, and oftentimes, each location is associated with specific pasalubong items, such as piaya from Bacolod or otap from Cebu. In Indonesia, Oleh-oleh refers to a similar tradition of similar importance, where a gift is given to friends and family after a trip. The oleh-oleh, like the pasalubong, is a visual representation of social bonds, a representation of the place the person visited, and is usually expected in the culture. Every place in Indonesia has their own oleh-oleh specialties, like bakpia from Yogyakarta, pempek from Palembang, and serabi solo from Solo.

Gestures in Common

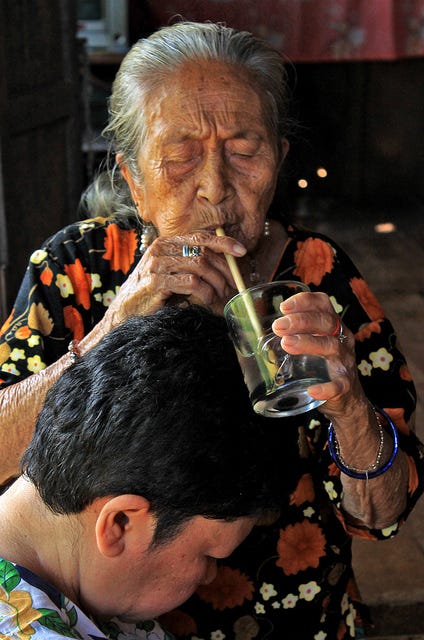

Respect for elders in both the Philippines and Indonesia can be best visualized by what is essentially the same cultural practice called Pagmamano or “Mano Po” in the Philippines and Salim Sungkem in Indonesia. In this practice, the younger person lowers their head in front of the elder, takes the elders hand and presses the back of the hand to their forehead. In both cultures, its a way to ask for blessings. The practice predates European colonization, and given the name, likely came around the time when Islam first spread in the archipelago4.

Shared Communal Dining Practices

Communal eating culture is another way that this community-oriented based culture manifests in the cultures of both countries. In particular, the custom of eating using banana leaf and with bare hands is the form of communal dining that is shared by both nations. The Kamayan feast of the Philippines (Kinamot in Visayan languages) shares a resemblance to the Megibung of the Balinese and the Ngeliwet of the Sundanese on the island of Java.

Interestingly, the Kanduli feast of the ethnic Maranao people in Mindanao uses dishes in the feast that bear a resemblance to the Slametan feast of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Madurese people, which oftentimes uses a tumpeng, or cone-shaped rice, namely nasi kuning, accompanied with side dishes.

Relaxed Standards for Time

Rather than being strict and punctual, time-fluidity is the norm in Southeast Asia, and this is very much seen in the two countries. This concept of time-fluidity is famously called Filipino time when describing the Philippines, and usually refers to things running late. Similarly, jam karet, or rubber time in Indonesia describes a similar situation where time can be stretched like a rubber. The mindset behind jam karet is one of flexibility whereas Filipino time takes on a more negative mindset.

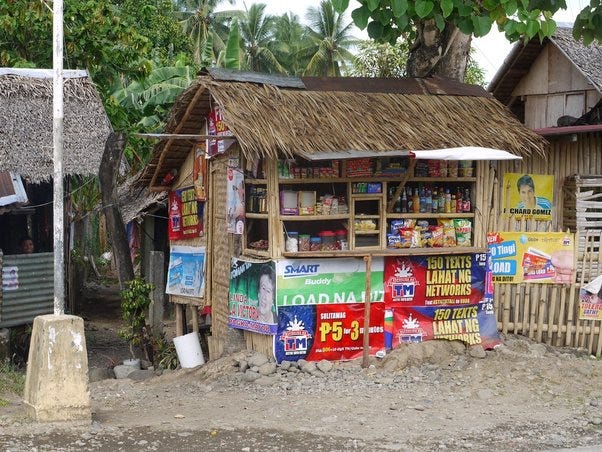

A Culture of Small Businesses that Serve the Community

In the presence of giant shopping malls in the cities, its the small, family-owned businesses oftentimes in buildings made of traditional materials that serve the needs of daily life in both the Philippines and Indonesia. The Sari-sari store is one such store in the Philippines. These small, family-owned convenience stores are ubiquitous in the barangays5 throughout the country, so vital to the nations economy these stores account for around 70% of sales of manufactured consumer products nationwide6.

The closest equivalent in Indonesia is the Warung, a local establishment that describes a variety of small businesses, many of them operate like a sari-sari store. The warung is operated by a local family and like a sari-sari store, is oftentimes operated at the shopkeepers residence. Among the different types of warung, the Warung rokok operates much like a sari-sari store in that it’s a miniaturized convenience store, whereas a Warung nasi that serves rice with other dishes, and a Warung tegal that specializes in Javanese dishes, operates and resembles Filipino-style Karinderias, where rice and ulam type dishes7 are served.

Common Architectural Features, Agricultural Traditions, and Maritime Navigation, and Facets of Urban Life

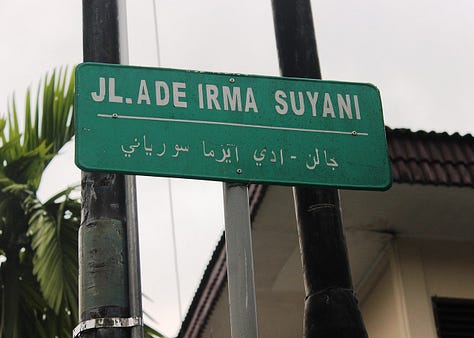

It is often said among Filipinos who travel to Indonesia and vice-versa that the appearance of both countries bear many striking similarities. Remove any signs in the local languages and more likely than not, it would become more difficult to tell if the surrounding scenery is in the Philippines or if they are in Indonesia.

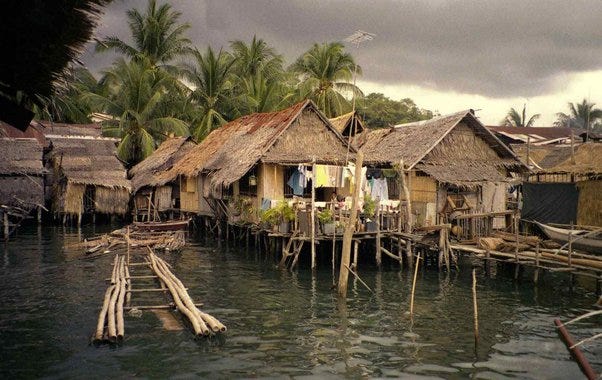

The Predominance of the Stilt-House in Traditional Vernacular Architecture

Most ethnic groups in the Philippines and Indonesia adhere to the traditional building techniques near-ubiquitous in Southeast Asia, and that is the existence of the stilt-house. A house raised on stilts, oftentimes built with natural materials like wood, bamboo, and rattan, are common vernacular architectural features in the building traditions of both countries. While largely absent in the building traditions of Javanese omah homes and Balinese houses, the stilt house is largely common amongst most other types of ethnic rumah adat in Indonesia.

The style of raised homes can even be found in more local royal architecture. The Pagaruyung Royal Palace of the Minangkabau people in West Sumatra is built in the rumah gadang style and is built on raised platforms. The torogan, a royal home that housed Maranao mobility in the southern Philippines follows a similar building tradition.

Agricultural Traditions and Production

The Philippines and Indonesia, despite now being heavily modern and rapidly urbanizing, are at their core, agrarian nations. Both countries have traditionally been involved in the production of rice, coconuts, bananas, mangoes, and coffee, and are even top producers of much of these goods on a global scale.

Today, both countries hold the #2 and #1 spot respectively, for most coconut production in metric tons, and are both the world’s main coconut oil exporters.

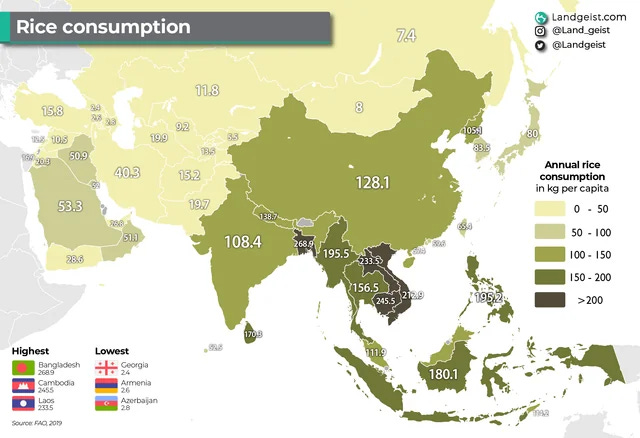

Rice fields, aside from palm fields, are a common sight in both countries. Indonesia was the 4th largest producer of rice in the world while the Philippines is the 8th largest. The countryside in both nations is often characterized by rice paddies, as rice is a staple food for many. Rice terraces make up a big part of the cultural landscape in both nations. The Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras built by the Ifugao people are considered an important cultural landmark of the Philippines whereas the Tegalalang Rice Terraces in Bali are part of a wider system of traditional water irrigation called Subak, primarily for rice production of the Balinese people8.

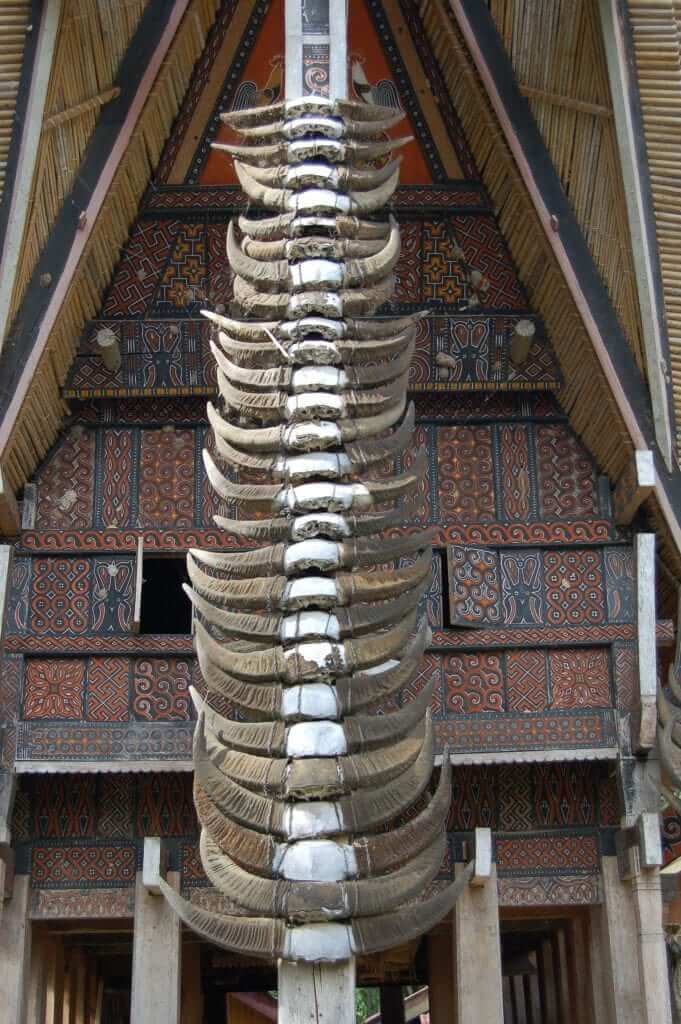

The water buffalo is a common sight in the fields of both nations and are important cultural symbols among the various ethnic groups. The carabao is a local variety of water buffalo in the Philippines, originally descended from swamp buffaloes in Taiwan, and has since spread onward to Borneo and Sulawesi9. The carabao is considered to be the national animal of the Philippines and are the traditional draft animals in rice fields. Carabao are a part of many harvest festivals, one of the most notable being the Kneeling Carabao Festival celebrated by the local Tagalog people in Pulilan, Bulacan to honor a local patron saint.

In Indonesia, water buffalo hold a place of high reverence among some ethnic groups. The Toraja people in Sulawesi sacrifice kerbau in their ceremonies. The Minangkabau people in Sumatra adorn their houses with motifs of the buffalo, and their traditional headdresses resemble those of a buffalo’s horns. An important legend of the Minangkabau people describes how their people won a water buffalo fight through wisdom and strategy.

Maritime Traditions

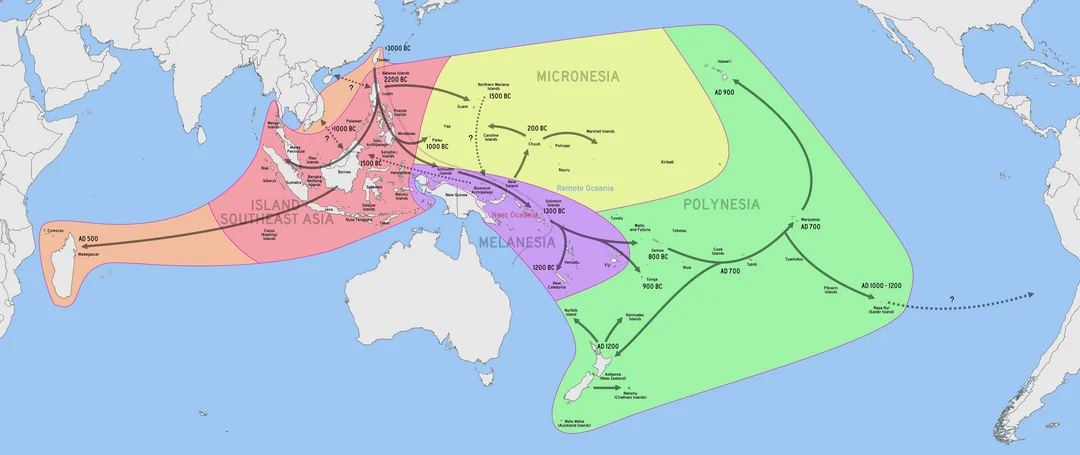

The islands of the Malay archipelago were populated in large part due to massive waves of Austronesian migration. Historically, Austronesians are known for their expertise in navigating the sea and building fast ships that can transport hundreds of people10, and with these special skillsets, they have been able to expand outwards through all of what is now maritime Southeast Asia, westward to Madagascar and eastward to the Pacific Islands.

Traditional shipbuilding traditions are shared between the peoples of the Philippines and Indonesia. On the smallest scale, the outrigger canoe is a common feature found in both nations. In the Philippines, it is known as the bangka. In Indonesia, it is generally referred to as the jukung. The paraw, a double outrigger sailboat traditionally found in the Visayas region of the Philippines is a cognate of the Malay term perahu.

The Sama-Bajau people, whose ancestral domain lies between the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, is an Austronesian ethnic group that encapsulates the maritime heritage of Austronesian peoples. Their life is primarily a life on sea, either in floating villages just off the coast or on boats11. From the Sulu Archipelago to the Togean Islands near Sulawesi, the Sama-Bajau live a semi-nomadic lifestyle, and their wide range across national borders is a testament to shared connections and common cultures across rigidly-defined modern nations.

Urban Life

One feature of urban life in Asia is the existence of megacities: sprawling metropolises that exceed over 10 million inhabitants. Manila, when taking into account its metro area reaches around 12 million inhabitants while Jakarta’s population sits at a little over 30 million. Much of the wealth of these respective nations are centered in these cities, but it is also in these cities where the wealth inequality is so blatant. Rich neighborhoods with tall condominiums rise above sprawling slums.

Specific modes of transport in the cities mirrors each other. Since the late 2010’s, Grab is the ride-hailing app that is popular all throughout Southeast Asia, but it is hardly the only mode of transport that connects the two nations. It is in Southeast Asia that you will find variations of a bicycle or motorized vehicle where a passenger cab is attached to it. In the Philippines, the tricycle is a ubiquitous facet of urban life and are a cheap, for-hire way to get around. Similarly, the bajaj in Jakarta has the same function, though its resemblance is closer to an auto-rickshaw. Outside of Jakarta, a bentor-style rickshaw is commonly used, though how it appears varies among cities.

Traditional horse-drawn carriages can also be found. The kalesa is a part of urban life in the Philippines though it’s more commonly associated with historic areas such as the Intramuros district in Manila and the colonial city of Vigan. In Indonesia, the andong is a similar concept specific to the city of Yogyakarta. Additionally, the cidomo is a local version of a horse-drawn carriage found in Lombok and the Gili Islands.

Another facet of urban life is the existence of giant malls, a common feature of many Asian cities, with major cities in the Philippines and Indonesia being no exception. In the urban centers of Southeast Asia, the mall is a social hub whilst also a spot to enjoy shopping in an air-conditioned environment.

Linguistic Connections

Both the Philippines and Indonesia share a high amount of linguistic diversity. In the Philippines, there are around 175 or so regional languages, the largest being Tagalog12, Cebuano, Ilocano, and Bikol, while Indonesia has over 700, the largest being the national language Bahasa Indonesia13, as well as Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, and Minangkabau. All of these languages fall under the Austronesian language family, specifically the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup of languages.

The similarities between languages can be seen in the many words that are shared in common. For example, the numbers for Tagalog and Javanese up to 10 are nearly identical to each other from numbers three to eight. The words for cheap (Tagalog: mura, Indonesian: mudah), expensive (mahal in both official languages), eye (mata in both official languages), love (sinta/cinta), nation (bansa/bangsa), illness (sakit in both official languages), child (anak in both official languages) and some pronouns (i.e ako/aku for “I”, kami/kami for “we”) are nearly the same in both Tagalog and in Bahasa Indonesia. Interestingly enough, the word for rice “nasi” in Bahasa Indonesia is the same as “nasi” in the Kapampangan language.

Even the introduction of loanwords from Spanish and Portuguese has made the words for door (Tagalog: pinto, Indonesian: pintu), table (Tagalog: lamesa, Indonesian: meja), and shoe (Tagalog: sapatos, Indonesian: sepatu) similar.

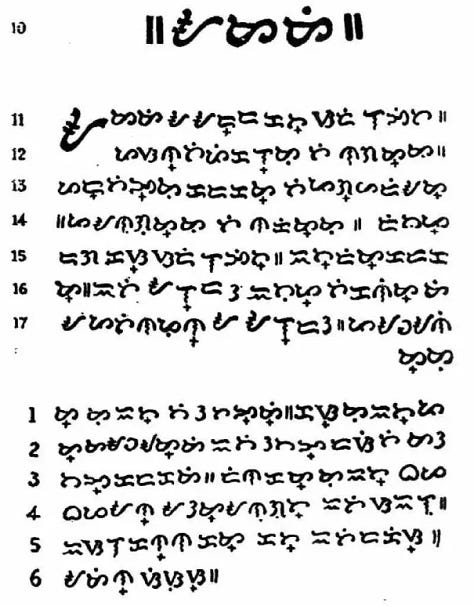

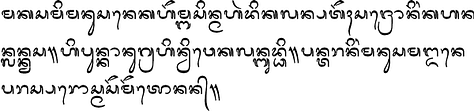

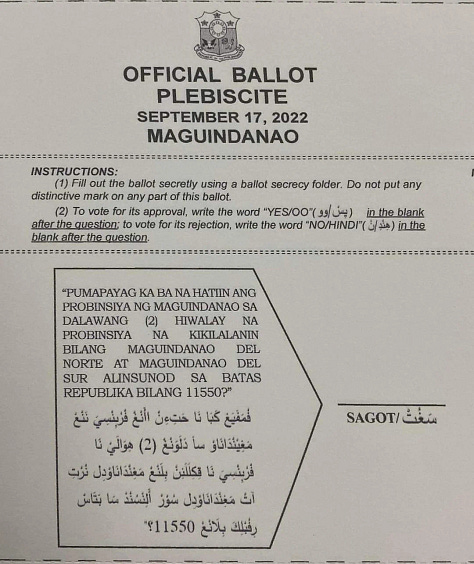

Writing Systems, from Brahmic to Arabic

Today, most languages in maritime Southeast Asia are largely written using the Roman alphabet, though historically, languages such as Tagalog, Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese were written using abugidas that fall under the Brahmic scripts, systems of writing that trace their origins to India14.

It is with the spread of Islam to the Malay archipelago that Arabic scripts have taken on a localized version in Southeast Asia, namely the jawi script. While the usage of the jawi script varies15, it has been used to write the languages of the Maranao, Maguindanao, Tausug, Acehnese, Malay, and Banjarnese, and any other ethnic groups who have adopted Islam.

Clothing, Weaving, and Blading Traditions

It’s no surprise that similar geographical features and centuries of trade and contact have forged similarities in clothing traditions between the two nations.

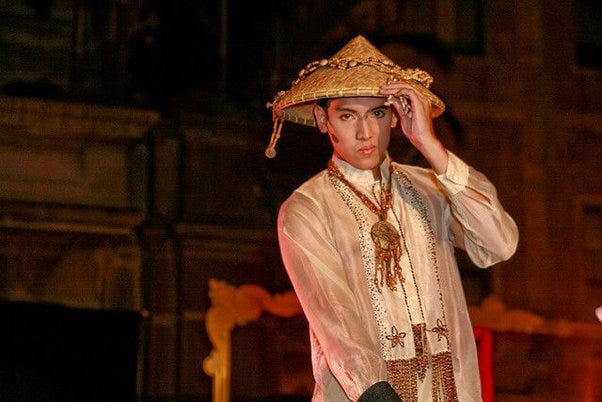

Headgear in Agricultural and Religious Contexts

The Asian conical hat is near ubiquitous in both East and Southeast Asia, oftentimes associated with farmers and laborers. Each country in Southeast Asia has their own local version of this hat, and may even have local variations depending on the region. The salakot16 is a general term for this type of hat in the Philippines, and while also traditionally worn by farmers, pre-colonial royalty have been known to wear it. This tradition has even continued into the colonial period with local principalia wearing tortoise shell salakot17. The Ilocanos have their own version of salakot made out of gourd names kattukong. In Indonesia, the hat is known by many names. Javanese refer to the hat as caping. Banjarnese people in South Kalimantan wear a local tanggui hat made of palm leaves, while the Acehnese create their local tudung using woven pandan leaves and bamboo.

A seraung is a local Dayaknese version of the conical hat in Kalimantan that is characterized with the addition of colorful fabrics. Similarly, the T’boli people in the southern Philippines have a similar hat tradition called s’laong kenibang, where a wide-brimmed hat is lined with red cloth in the t’nalak style.

Ethnic groups in both the Philippines and Indonesia that have adopted Islam have adopted the songkok or kopiah, a cap. In Indonesia, the songkok is considered to be one of the national dresses and is often seen worn by prominent figures, whereas the songkok in the Philippines is mostly relegated to the traditional clothing of Muslim Filipinos, particularly the Maranao, Maguindanao, Yakan, Tausug, and other ethnic groups that fall under the term “Moro”.

The Baju Melayu and the Sarong

The traditional Malay clothing for men that originated in the court of Malacca Sultanate has since spread to parts of Indonesia as well as the southern Philippines. While there are regional and ethnic varieties of the baju melayu, the main components include the baju, a long-sleeved shirt, celana or seluar trousers, and a wrap skirt known as a sarong. The baju melayu enjoys widespread popularity in Indonesian provinces with significant ethnic Malay populations such as Riau18 and West Kalimantan, and the ethnic Betawi people native to Jakarta have their own versions.

The wrap skirt is widespread around Southeast Asia, and is generally referred to as a sarong. In the Philippines, the sarong goes by different names, such as the tapis19 in Luzon, patadyong in the Visayas, and the malong in Mindanao. In Indonesia, the wrap skirt is generally known as the kain sarung, and in Bali it is locally referred to as a kemben. The sarong is traditionally seen as a unisex clothing.

Interestingly, the term “baju” in Malay is a cognate of local term for “baro” in Tagalog, with the “baro” being part of the Barong Tagalog and Baro’t Saya20, the national dress of the Philippines.

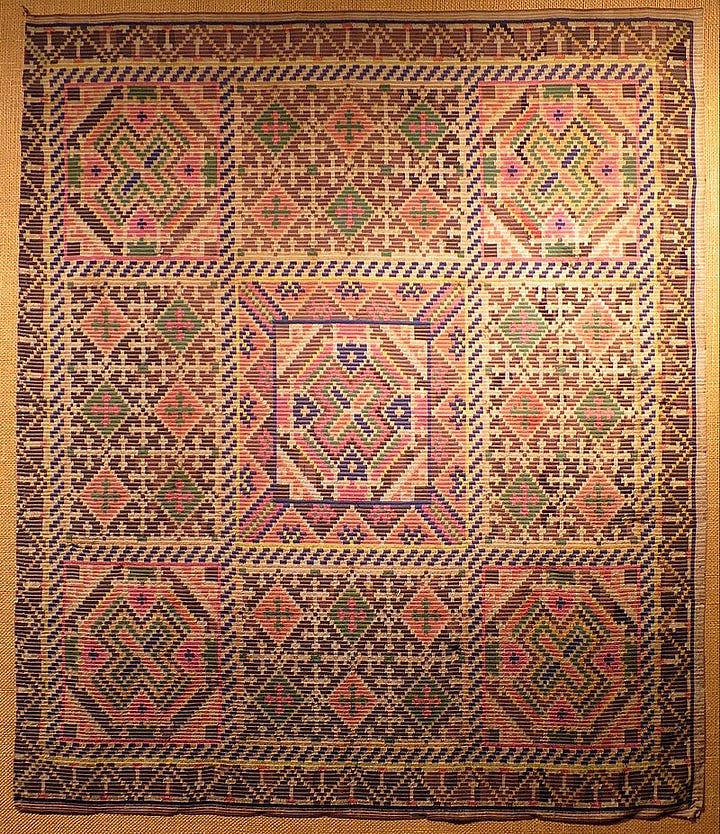

Traditional Weaving Practices and the Use of Gold Fabric

The term ikat, an Indonesian term, is widespread among Southeast Asia and refers to a dyeing technique that uses resist dyeing to create patterns and color fabrics. The indigenous peoples in the Cordilleras as well as in Mindanao in the Philippines practice their own variation of ikat weaving. The oldest example of ikat dyed cloth in Southeast Asia have been found in the Philippines called the Banton Cloth and date to around the 13th century. Indonesia is one of the few countries where double ikat is produced, and are considered prized textiles.

Gold fabric weaving is also another textile tradition that is found in both nations. In the Maguindanao weaving tradition, inaul is a handmade fabric that uses a blend of silk and gold threads infused into cotton threads to create brightly-colored malong as part of their traditional clothing. Similarly, songket is a weaving tradition that uses hand-woven silk or cotton and intricately patterned gold or silver threads. The tradition of songket dates back to the Srivijaya Empire, a maritime trading empire based in Sumatra, where the tradition remains part of the local identity.

Austronesian Tattooing Traditions

Among some of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines and Indonesia, a culture of hand-tapping tattooing has been practiced for centuries and in some cases, has undergone a revival. Kalinga-style tattoos from the Kalinga people in the northern Philippines is one such tattooing tradition, largely in part due to Whang-Od and her community. Batok is a general term for indigenous tattoos in the Philippines. Similarly, traditional Dayak tattoos from Borneo have experienced some revival of tattooing traditions, which also involve a similar method of hand-tapping.

Common Blading Traditions

The kris sword, known for its wavy blade, originated in Java and through contact, has spread to other parts of Southeast Asia due to the influence of the Majapahit Empire21, and has become a traditional blade in the Philippines as well. The kris has historically been part of the traditional regalia for many sultans. Traditional kris making continues in the Javanese cultural heartland. The kalis, a variation of the kris used in the southern Philippines has been seen as a symbol of resistance to colonialism and today is incorporated into the flag of the autonomous Bangsamoro region.

.

Games and Pastimes

Mancala is a traditional board game that has a wider reach within Asia, and that is especially true in both nations. In the Philippines, sungka refers to a mancala-type game that in 1642 was observed to be played with sea shells on a wooden, boat-like board. Aside from being a game of strategy, the sungka board has been used in divination and fortune telling. Dakon is a local variant played by the Javanese in Indonesia, with the rules not differing too much from Sungka. In 1817, Dakon was described by Sir Raffles as a game played primarily by women. Congkak is another term for the game and is often the name used in Malaysia and Brunei.

Sepak takraw is another game that also has a wide reach around Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, sipa is the local version of sepak takraw, and like the sepak takraw version, uses a rattan ball and involves kicking the ball up in the air. It was considered the unofficial national sport until 2009. There is a local Maranao version of the sport called Sipa Salama, which involves a protective wooden piece on the foot and a sash that is used as a whip each time the ball is hit. In Indonesia, a local version of sepak takraw is sepak raga, and in Nusantara takes on several local versions.

A local version of greasy pole exists in both countries. Palosebo in the Philippines uses a long bamboo pole with a prize attached to the top. In Indonesia, Panjat Pinang is oftentimes associated with Independence Day and has largely the same rules. Both versions of the game are believed to have been introduced during their respective colonial eras22.

Cockfighting in Southeast Asia goes back to ancient times. Sabong in the Philippines remains a common pastime and form of gambling. The game was recorded in the islands as early as 1521 when Magellan’s crew witnessed a sabong match in the ancient kingdom of Taytay in Palawan. In Indonesia, the Balinese have practiced Sabung Ayam since the 10th century according to Batur Bang Inscriptions, and takes on a religious purpose as it is considered a ceremony in Balinese temples.

A game of tag involving a rectangular grid and teams of two can also be found in both countries. The game is referred to as patinero or tubigan in the Philippines, but depending on the local language may have a different name, such as alagwa in Kapampangan or sinibon in Ilocano. The objective of the game is to go back and forth between rectangles without getting tagged, and the taggers only stay on the lines. In Indonesia, gobak sodor refers to a similar game with similar rules.

Traditional Music and Dance

Gong and Percussion Ensembles

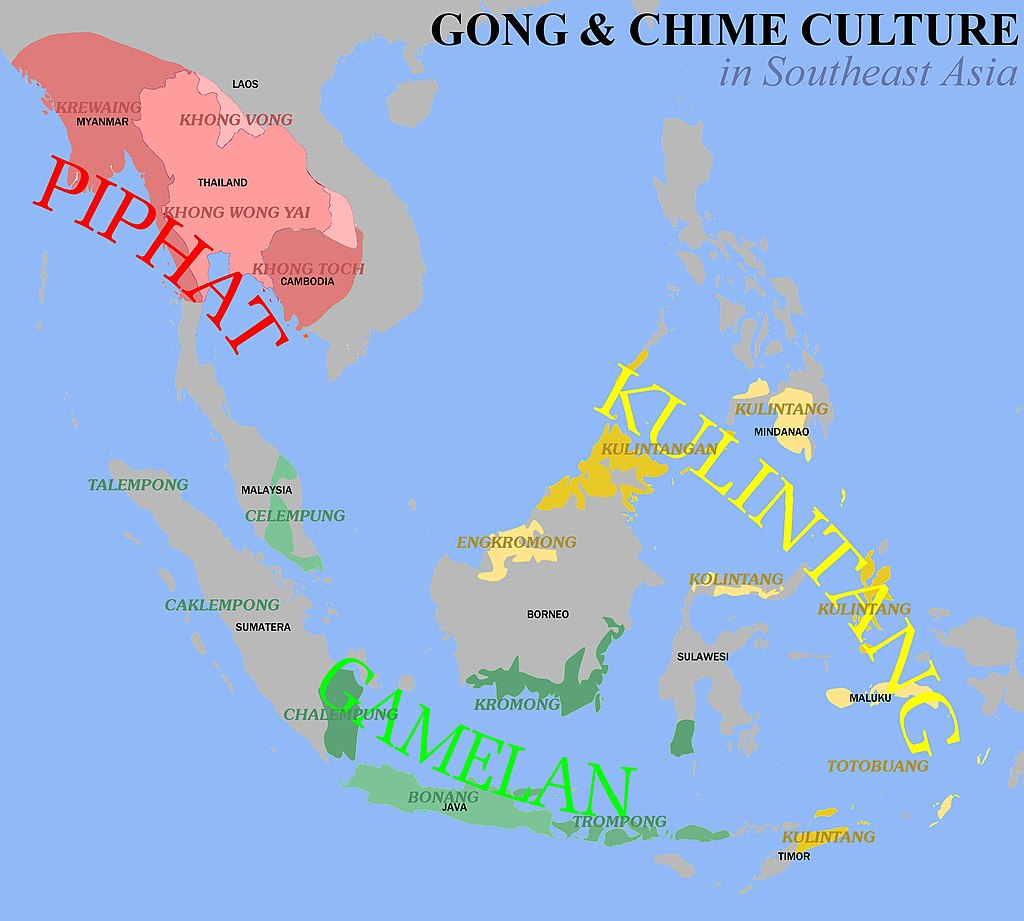

A unique feature of Austronesian traditional music is the gong ensemble. The use of gongs in traditional music transcends many cultures within Southeast Asia, and gong ensembles are plenty in the countries that make up the Malay Archipelago. Traditional gong instruments can be single large gongs, suspended gongs, or a melody of organized, smaller gongs.

Kulintang is one of three of Southeast Asia’s major gong ensembles, the other two being gamelan, primarily found in Western Indonesia and Bali and piphat found in Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos.

The kulintang is the most widely recognized form of gong ensemble in the Philippines, and makes up the traditional musical traditions of the southern Philippines, particularly among Muslim23 and Lumad24 Filipinos. The tradition of kulintang is even found in parts of Indonesia also goes by various names like kulintanang in the Sulu Archipelago and Borneo and totobuang in Maluku, Indonesia. Gamelan25, much like kulintang, has a significant cultural and historic value in Java and Bali. There is even a Javanese saying that goes “It is not official until the gong is hung.” These gong ensembles are even used in religious and spiritual ceremonies throughout maritime Southeast Asia26.

Hanging gongs are another facet of gong culture prevalent in both nations. The agung in the southern Philippines accompanies the kulintang27, while the kempul is used in Indonesian gamelan. In this context, these hanging gongs act as supporting instruments in a wider ensemble.

Other percussion instruments include the use of bamboo xylophones, known locally as gabbang in the Philippines and kolintang in the Minahasan region of North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Gambang, another variety of xylophone, is made of hardwood and is often found in Balinese gamelan emsemble.

Traditional Lutes

Boat lutes, also known as kudyapi, are a two-stringed instrument found in various cultures in the Philippines as well as the island of Borneo, namely the Dayak people found in the Kalimantan region of Indonesia. In South Sulawesi, kacapi is the term by the Kajang people to describe the boat lute, though the name has slight variations28 around Sulawesi.

Bamboo Stick Dances

Among the many bamboo stick dances found throughout Southeast Asia and a little bit into the southern Yunnan region of China and northeastern India, Tinikling oftentimes takes a front-and-center presence. This Visayan traditional dance is often the face of bamboo stick dances, so much so that this type of dance tradition is most commonly associated with the Philippines. Given the wide geographical range of this dance tradition, Indonesia has a few of its own variants as well. Tari Gaba-gaba of the Maluku islands is one of the local versions29 of the dance.

Balancing Acts

Certain traditional dances in the two countries involve balancing objects like candles, glass, or plates.

Pandanggo sa Ilaw is a traditional candle dance from Mindoro that involves dancing and balancing candles. Tari Lilin is a similar dance from the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra, though this dance may also include balancing plates.

Binasuan is another balancing dance in the Philippines which involves balancing glasses filled with liquids, where dancers rotate their arms whilst holding the items without dropping them. Tari Piring from West Sumatra involves balancing plates on arms and involves rapid movements, though in this dance, the plates are intentionally broken at the end of the dance.

Echoes of War

War dances which involve the use of weapons and shields as props are still seen among some of the indigenous peoples of both nations.

Many dances of the Igorot peoples30 in the northern Philippines such as the Kalinga, Bontoc, and Ifugao people depict acts of war and utilize traditional weapons and shields. The Idaw dance of the Kalinga depicts a headhunting expedition. Other dances that use swords and shields in the southern part of the Philippines include the Sagayan dance of the Moro people and the Saot dance of the Higaonon people. Kabarasan is a traditional Minahasan war dance of North Sulawesi also uses swords and shields, and is meant to imitate a pair of fighting roosters. On the island of Maluku, the Cakalele dance involves a mock-duel with traditional spears and a shield, and originated as a way to celebrate a successful raid.

Spirituality, Religious Ties, and Legends

In Southeast Asia, nature spirits are highly revered and respected. This manifests in many different ways, from the designation of sacred trees to offerings and the construction of spirit houses.

The Banyan Tree

A common theme among the many nations of Southeast Asia, the Philippines and Indonesia included, despite differing religious beliefs among the nations, is the sacred nature of the banyan tree31. This tree, with its adjacent prop roots that allows it to spread outwards, holds significant spiritual connotations. In the Philippines, the banyan tree is locally known as the balete tree, and is believed to be the home of many diwata and supernatural beings like the kapre and tikbalang. In Indonesia, the banyan tree appears in the national coat of arms. In Bali, offerings are often left at the foot of banyan trees32 as they are believed to have resident spirits. Balinese tradition dictates that trees wrapped with a poleng cloth33 are sacred and provides blessings.

Sacred Decorations and Offerings of Natural Materials

A common sight in many religious places and sacred grounds are offerings. Woven palm and palm art is one kind of offering that is shared in the religious and spiritual traditions of the Philippines and Indonesia. Palaspas, a tradition of woven palm art in the Philippines, is especially important on Palm Sunday, and is one of many examples of a pre-colonial religious practice that has blended with Catholic traditions. Lamak are woven palm mats found as offerings to deities and ancestors as well as decorations for altars and shrines in Bali. Like the palaspas, the lamak are used for a particular celebration, in this case, the Galungan festival.

White jasmine is another material used as offerings but also bears cultural significance. Known as sampaguita in the Philippines and melati in Indonesia, it is considered to be the national flower of both nations34. Often used as decoration in clothing35 and perfumes, the white jasmine is also an important part of religious and spiritual ceremony. Statues of the santos in many Catholic churches in the Philippines can often be seen adorned with white jasmine. Balinese Hindus in Indonesia use the white jasmine in many offerings, particularly in the canang sari36, a daily offering of gratitude seen in shrines and temples to gods.

Carvings of the Ancestors

Various traditions in both archipelagic nations include the use of wooden, carved figures that represent local deities and the ancestors. While the tradition varies, the appearance of these wooden figures bear many visual similarities, from their often austere appearance to the postures such as standing upright or sitting with arms folded over raised knees.

The tradition of anito sculptures was once widespread37 in the Philippines but largely survives among the Igorot peoples of the Cordillera Mountains. In their cultures, the bulul is believed to guard the rice crop and are representations of the ancestor spirits. Similar traditions exist within Indonesia. Dayak peoples in southern Borneo have hampatong as personifications of a particular ancestor spirit or deity. Similarly, the luli dera refers to a similar tradition in Maluku, and the tau tau figures of the Toraja in Sulawesi represent ancestors guarding tombs and protecting the living. The adu are seated ancestor figures of Nias Island, and more refined representations of the ancestors known as siraha siwala or siraha nomo were reserved for the local aristocrats.

Legends from Hindu-Buddhist Traditions

Since pre-colonial times, Hinduism and Buddhism have made waves throughout Southeast Asia, and have been influential in the many kingdoms of what is now Indonesia and the Philippines. While Animism has largely been the dominant belief system in pre-colonial Philippines, Hindu and Buddhist beliefs have made their way to the ancient kingdoms in the Philippines through trade and contact, mostly indirectly through local kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago. An example of this is the word diwata, used to describe the nature spirits in the Philippines, has cognates in Indonesian languages such as dewata in Javanese and debata in Toba, all of which are derived from the word devata in Hinduism.

In many traditions in Southeast Asia, the naga is a serpentine dragon that inhabits the waters and originated from Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The Bakunawa in Visayan mythology was syncretized with the Naga, and is believed to bring eclipses, earthquakes, rains and wind. It is most known for swallowing the moon. The Bakunawa draws similarities to the Hindu demi-god Rahu, a figure who has spread to Javanese traditions. In Balinese tradition, Kala Rahu is seen devouring the moon goddess Dewi Bulan, representing a lunar eclipse. The representation of Bakunawa can be seen on the hilts of traditional tenegre swords.

Other visual representations of the naga in the Philippines can be seen in panolong designs, which are often seen on the side of Maranao torogan homes. These naga are depicted in the okir style, a local geometric style of art among many Muslim Filipinos. Naga take on various representations throughout Indonesia, as crowned serpents, human form in Borobudur, or even created with the likeness of Chinese dragons.

The garuda, another figure of Hindu and Buddhist legends, is a divine eagle-like sun bird and king of birds and takes on many forms. Evidence of Hindu-Buddhist influence has been found in the Philippines in the form of local mythology like the Garula of Kapampangan legends38 and the belief of winged creatures in Maranao legends, as well as physical representations made of gold. The garuda in Indonesia is considered to be a national symbol, as well as a cultural symbol in Java and Bali as a nod to their Hindu heritage. Garuda are seen as emblems in many institutions in Indonesia and are seen as a unifying symbol in a nationalist context.

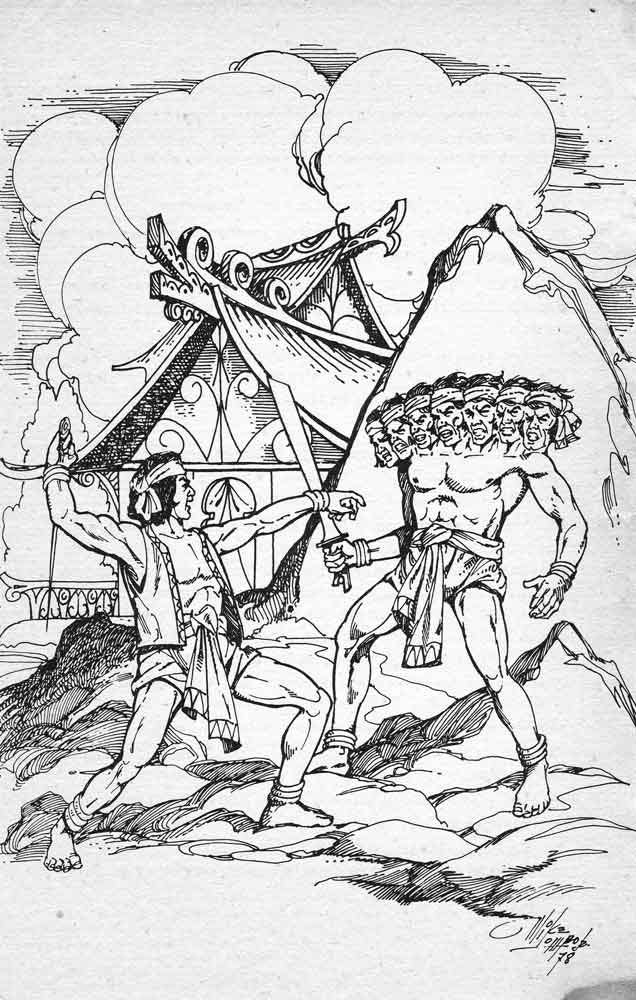

The Ramayana, an epic tale originating from India, has made waves and taken on many local variations in Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, the Maharadia Lawana is the local version of this tale told by the Maranao people. The tale is told by public epic chanting, a widespread tradition in the Philippines, and often takes days to recite. This version of the Ramayana is based on the adaptations found in Indonesia and Malaysia. There are several adaptations of the Ramayana in Indonesia such as the Javanese Kakawin Ramayana and the Balinese Ramakavaca, with some local dances like the Balinese kecak and wayang kulit retelling the story with dancers playing characters.

Indigenous Beliefs and Shamanism

Though organized religions Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism on the island of Bali dominate the Philippines and Indonesia, a huge undercurrent of Animism still resides and blends with the traditions of the dominant organized religions. Alongside animism and ancestor worship, shamanism still remains strong as they are seen as traditional healers.

Babaylan is a common term for the many shamans among the various ethnic groups in the Philippines. The term babaylan is a cognate of many similar words in maritime Southeast Asia that refer to shaman, such as walian in Maranao, walyan in Old Javanese, balian in Balinese, and balien in Makassar. Their primary role is to interact with deities and the spirit world, as well as act as mediums and take part in healing, divination, and sorcery. Similarly, the albularyo in the Philippines focuses on folk healing and traditional medicinal practices. Siquijor Island is notorious for the albularyo, as many people come to them to receive spiritual services and healing. In Indonesia, the role of a dukun is similar to an albularyo, where their role is that of a traditional healer and a spirit medium. The dukun remain an important part of Indonesian society, as many highly prominent individuals have consulted dukun. The islands of Java, Madura, and Bali are known to have a large amount of dukun, with some having a reputation of using dark magic.

Culinary Traditions and Cooking Methods

Cooking Tools and Fermentation

The wok, believed to have originated from South Asia or China, is a staple in Southeast Asian kitchens. This giant, deep round-bottomed cooking pan goes by different names and has some slight variations depending on the country. Within the languages of maritime Southeast Asia, the wok is called kuali (small wok) in Malay, wajan in Javanese, kawali in Tagalog, kalaha in Cebuano and talyasi in Kapampangan.

Fermentation in the traditional method for rice and other starchy foods like cassava and potatoes is a shared method of preservation, and is called tapai. Many cognates of the word exist in the Philippines and Indonesia, such as tempayan in Javanese and Malay, and tapayan in Tagalog and Maguindanaoan. These starches are traditionally fermented in tapayan jars, and the tapai can have many end products like rice cakes and desserts39, as fermented rice served with seafood, or used in rice wines40.

A large, woven tray made of bamboo for winnowing rice, holding and serving food is another culinary tool the two countries share. The term for this tray is called bilao in the Philippines while it is called tampah in Indonesia. The item has traditionally been used in the kitchen but has recently taken on a decorative element.

Rice and its Versatility

It goes without saying, rice is an important staple crop and shows up in nearly every meal in Filipino and Indonesian cuisine. Nasi goreng, or fried rice, is one of Indonesia’s five national dishes. Local karinderia’s in the Philippines always serve rice alongside an ulam, or savory-type dish. Rice shows up in local cuisine in various ways, fried, as a porridge, as a side, as rice noodles, as crackers, and as various rice cakes in desserts.

Rice wrapped in intricate woven palm pouches is a shared tradition among the countries of maritime Southeast Asia. The term widely used in the Malay Archipelago is ketupat, but the wrapped rice takes on various names depending on the language. In Indonesia, ketupat can be referred to as kupat in Javanese and Sundanese, and tipat in Balinese. In the Philippines, ketupat takes on various names such as puso in Cebuano, ta’mu in Tausug, and patupat in Ilocano. Ketupat is oftentimes associated with religious holidays and traditions, such as Hari Raya for Muslims and Galungan holy days for Balinese Hindus.

Rice cakes in the Philippines are collectively branched under the term kakanin. The main ingredient for these is a sticky rice locally called malagkit41 in Tagalog, which creates a smooth rice dough called galapong. Popular kakanin include puto, bibingka, sapin-sapin, suman, and kutsinta. In Indonesia, the term kue42 refers to bite-sized snacks or desserts, many of them containing rice flour43. Some of the most popular kue in Indonesia that fall into rice cakes made of glutinous rice, or beras ketan, are kue putu, onde-onde, kue lapis, and kue wajik.

The word puto is a cognate of the word ‘putu’, a term used in many rice cakes in Malaysia and Indonesia, with origins in the Tamil word ‘puttu’, a Tamil steamed rice cake. Kue putu in Indonesia is prepared the same way as puto bumbong in the Philippines, steamed in a bamboo tube44.

Dodol, a sweet toffee-like dessert made with rice flour, carries significant religious connotations. In the Philippines, dodol is a huge part of Ilocano food heritage, and is a popular item to be used as food offerings for Undas. Dodol is also the main delicacy of Guling-Guling, the Ilocano version of Fat Tuesday before the Lenten season begins. Among Muslims in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia, dodol is a common sight for festivities during Ramadan, and most commonly prepared during iftar, a meal to break the fast.

Cassava as a Staple

Cassava is another staple in both countries, though less so than rice. Cassava is mainly used in desserts in the Philippines and locally referred to as kamote, with dishes such as cassava cake or bibingkang kamoteng kahoy, pitsi-pitsi, and salbaro. In Indonesia, cassava takes on a wider role and can be used in savory dishes as well as in desserts. Known locally as singkong or ketela, cassava is used in desserts like getuk and peuyeum, and in savory dishes such as gulai daun singkong, buntil, and tiwul, crafted from dried cassava.

Common Ingredients and Condiments

The culinary traditions of the Philippines and Indonesia share a lot in common. Among common ingredients, coconut milk is often a recurring theme in dishes found in both countries and in the rest of Southeast Asia, from savory to sweet, and sometimes spicy. Generally speaking, any dishes cooked in coconut milk is referred to as ginataan in the Philippines, such as the savory ginataang langka and ginataang manok to the sweet ginataang bilo-bilo and ginataang mais. The use of coconut milk is seen in many Indonesian dishes like rendang as well as a couple varieties of soto, a soup that’s regarded as one of Indonesia’s national dishes, to desserts like serabi and kolak.

Seafood byproducts are also important aspects of local cuisine. Fish sauce is one of those quintessential ingredients in Southeast Asia, with countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia being major producers of the condiment. In general, fish sauce is known as patis in the Philippines, while it is known as kecap ikan in Indonesia. Shrimp paste is another popular condiment, often adding a bolder flavor to food or included as a side. Bagoong refers to condiments in the Philippines made from salted or fermented shrimp, with the excess liquids used to make patis. Indonesia has a few varieties of shrimp paste, including terasi( Javanese: ꦠꦿꦱꦶ) in Javanese cuisine, petis udang, and belacan.

Some common plants and vegetables associated with Southeast Asian cuisine and ingredients that are commonly found in Filipino and Indonesian cooking are lemongrass (tanglad in Tagalog, serai in Bahasa Indonesia)45, pandan, tamarind (sampalok in Tagalog, asam jawa46 in Bahasa Indonesia), galangal (langkawas in Tagalog, lengkuas in Bahasa Indonesia), water spinach (kangkong or kangkung in the many languages of maritime Southeast Asia), bamboo shoots (labong in Tagalog, rebong in Bahasa Indonesia), and chilies (sili in Tagalog, cabai in Bahasa Indonesia).

One of Southeast Asia’s most famous ingredients, lemongrass is generally used in savory dishes, used in many soups, curries, and sate dishes. Pandan juice is typically extracted from its leaf and acts as a food coloring, mainly in desserts like pandan cake, lapis legit, and buko pandan. Tamarind typically acts as a souring agent, particularly in soups like the Filipino sinigang and Indonesian sayur asem.

Vegetables such as kangkong and bamboo shoots are often used in stir-fry dishes like Indonesian cah kangkung or Filipino ginisang kangkong, or cooked with coconut milk, such as Indonesian sayur lodeh (mixed vegetables in coconut milk) and Filipino ginataang labong (bamboo shoots cooked in coconut milk).

Both countries have their own variation of chilis, such as siling lambuyo and siling haba in the Philippines, and cabai hijau besar and cabai rawit47 in Indonesia. Chilis are used as condiments in the cuisine of both countries, with with around six or so different types of chilis being used for the many varieties of sambal (Javanese: ꦱꦩ꧀ꦧꦼꦭ꧀)48 in Indonesia. In the Philippines, siling labuyo is one of the most commonly used chilis, and is typically used in sawsawan49, or in condiments like local spiced vinegar and palapa, a local condiment50 integral in Maranao cuisine.

Originally derived from the Indian achar, the pickled vegetable condiment has its own version in Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, atchara is a pickled condiment made primarily from unripe papaya, and is usually served on the side of grilled dishes. While papaya is the most common ingredient in atchara, the condiment can be made with other vegetables like bell pepper, bamboo shoots, and ginger. In the rest of maritime Southeast Asia, acar refers to a similar method of pickling vegetables. In Indonesia, acar is made from chunks of varying vegetables as well as chili, and like its Filipino counterpart accompanies grilled foods.

Originally hailing from China, soy sauce is another popular condiment and sauce used in cooking. Local versions and brands of soy sauce exists in both the Philippines and Indonesia. Datu Puti is the household name brand soy sauce in the Philippines, and is often used to make adobo. Soy sauce in the Philippines is oftentimes mixed with calamansi and vinegar to be served as a condiment. Indonesia has kecap manis, a sweet soy sauce and kecap anis, a salty soy sauce. Popular brands of kecap manis include Kecap Manis ABC, Sedaap, and Kecap Bango.

Chinese Influence

Waves of migration to maritime Southeast Asia as well as centuries of contact, trade, and establishment of tributary states have left a huge mark in the local cultures of the Philippines and Indonesia, especially in their respective cuisines. The connection to China goes far back enough that some of the oldest Chinese diaspora populations can be found in Southeast Asia51. Chinese settlers, many of them hailing from Fujian, came to both the Philippines and Indonesia and have been known to set up businesses52, many of them around food. Today, many iconic dishes from the Philippines and Indonesia come from the Chinese diaspora.

Among the many foods of Chinese origin now part of local cuisines include spring rolls, noodles, shumai, baozi, rice porridge, and desserts such as hopia, jian dui, douhua, grass jelly, youtiao, and nian gao.

Fried spring rolls are locally known as lumpia in both countries, originally a Hokkien term53. A fresh version of lumpia that is not fried is called lumpiang sariwa in the Philippines, and popiah in Indonesia.

Noodle dishes in both the Philippines and Indonesia are as varied as the nations themselves. Pancit is a general term to describe local noodle dishes in the Philippines, with many of them made from rice noodles including pancit bihon, pancit canton, and pancit palabok. In Indonesia, noodle dishes are usually grouped under the term mie, with dishes such as mie goreng, mie ayam, and soto mie.

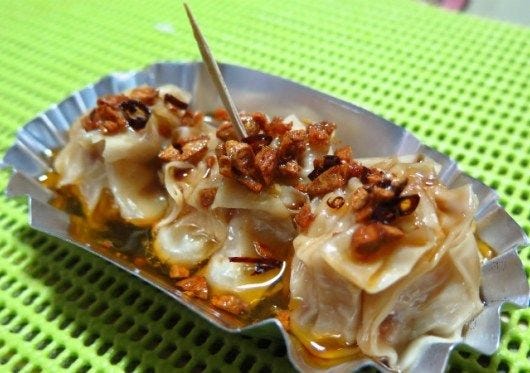

Shumai is locally known as siomai in both nations, and is often seen as a street food. A major difference in preparation is Indonesian siomai typically doesn’t use ground pork to fit halal diets. Baozi, or steamed buns, is locally known as siopao in the Philippines, and bakpau in Indonesia, and can be eaten as street food from hawkers.

Rice porridge dishes are typically regarded as comfort foods. Lugaw is a general term for rice porridge dishes in the Philippines, and are a typical breakfast food. Savory lugaw54 in the Philippines includes goto and arroz caldo55, while sweet lugaw includes champurado and ginataang munggo. Bubur is a general term for porridge or congee dishes in Indonesia, and like their Filipino counterpart acts as a popular breakfast dish. Rice porridge dishes in Indonesia includes bubur ayam, the most common form of bubur in the country and tinutuan, and desserts like bubur kacang hijau and bubur ketan hitam.

Hopia, a bean-filled mooncake-like flaky pastry, was introduced by immigrants to Fujian and is now a common snack in both the Philippines and Indonesia. Bakpia pathok (Javanese: ꦧꦏ꧀ꦥꦶꦪꦥꦛꦸꦏ꧀) is a localized version made in Yogyakarta, and is one of hopia’s most popular varieties in Indonesia. Mung bean is one of the most popular fillings for flaky hopia and bakpia in both the Philippines and Indonesia.

Jian dui, or deep-fried sesame balls, is another snack made of glutinous rice flour that made its way to Southeast Asia. In the Philippines, it is locally known as butsi and is associated with Chinese Filipino cuisine, and a staple in many local Chinese restaurants. Local versions of butsi may have red bean or ube filling. The snack in Indonesia is called kue onde-onde or kue moci56.

Douhua, a Chinese dessert made of silken tofu, also takes on iconic status in localized forms. In the Philippines, taho is a popular breakfast item and is most commonly associated with vendors who sell taho door-to-door. Sago pearls and brown sugar syrup are added, giving taho its unique appearance. The dessert is known as kembang tahu or wedang tahu (ꦮꦺꦢꦁꦠꦲꦸ) in Java, and is also sold by hawkers. Wedang tahu is served with palm sugar syrup and ginger.

Grass jelly, originally made by the Hakka people in southern China, was introduced to Southeast Asia by Chinese diaspora populations. Known locally as gulaman, many Filipino desserts and refreshments incorporate grass jelly, in drinks like sago’t gulaman, fruit salads, or even in buko pandan. In Indonesia, this ingredient is known as cincau57 from the Amoy Hokkien word, and is also used in desserts or drinks.

Youtiao, or Chinese fried dough, is commonly seen as a street snack in Southeast Asia. Bicho-bicho is the local name in the Philippines, while cakwe is generally what it is referred to in Indonesia. Bicho-bicho is typically eaten by itself while cakwe can be eaten alongside dishes like bubur ayam.

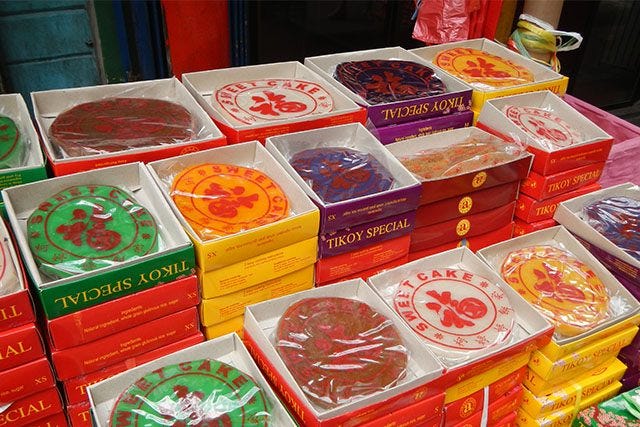

Nian gao is another rice cake made form glutinous flour, and is commonly associated with Chinese New Year. Tikoy is the local name of the rice cake in the Philippines, the term originating from Hokkien. It also goes by a few other names in Indonesia, such as kue keranjang or dodol Tionghoa or dodol Cina. It is sometimes called China cake because of many of the producers come from China.

The Austronesian Tradition of Roasting Whole Pig

One important aspect of Austronesian culture is the tradition of roasting whole pig, a practice done from the Philippines, to Indonesia, and all the way to Hawaii. Native pigs are one of the domesticated animals Austronesians carried throughout their expansions through Southeast Asia and into Polynesia.

While it is known in its Spanish-derived term, lechon also goes by various other names in the Philippines and was actually recorded in the 1521 expedition. The native Tagalog term for the dish is inihaw na baboy, while Visayans have traditionally called it inasal. Visayan lechon is the most famous of all the lechons in the Philippines, and typically uses herbs, garlic, salt, and lemongrass. Lechon is typically reserved for special occasions and holidays. Many Indonesian ethnic groups have a similar tradition, particularly in Christian communities in northern Sumatra and Sulawesi, and among Balinese Hindus. The terms ‘babi’ and ‘baboy’ are cognates of one another. Babi Guling in Bali is often served with lawar and steamed rice. The Batak people consider babi guling an important part of wedding offerings to the brides family.

Seafood

Being archipelagic nations, it should come as no surprise that seafood comes in abundance and is an integral part of local cuisine. From local tropical fish, to crabs, squid, shrimp, and even sea snails, traditional markets all over both the Philippines and Indonesia are typically teeming with fresh catches.

There is the classic grilled fish. Milkfish is grilled to create daing na bangus in the Philippines. Similarly, ikan bakar is used to describe dishes made of grilled fish in Malaysia and Indonesia.

There are even similar traditions of cooking whole crab in sauces. Curacha in Zamboanga, a city on the island of Mindanao is cooked with Alavar sauce, a blend of coconut milk, crab roe paste or taba ng talangka, and spices. Kepiting saus Padang, a local crab dish from Padang in West Sumatra douses the crab in a spicy Padang sauce.

While shrimp has its varying uses, one notable way shrimp is served and prepared is when its cooked in coconut milk. Ginataang hipon is whole prawns in Filipino cooking that is cooked in typical Southeast Asian fashion, with gata or coconut milk, fish sauce, shrimp paste, and lemongrass, and occasionally spiced with sili labuyo. Similarly, Peulemak udeung is a local Acehnese dish where tiger shrimp is cooked in a thick coconut milk and flavored with a variety of local spices.

Satay

Satay, or grilled and marinated sticks of meat, is one of the most famous dishes that comes from Southeast Asia, widely eaten in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In fact, it is considered one of five of Indonesia’s national dishes. Satay is typically served with a side of peanut sauce, and is one of the most popular street foods that unites a vast amount of culinary traditions. Satay is locally known as satti in the southern Philippines, particularly among the Tausug people. It is served alongside a local version of ketupat called ta’mu in Tausug and like its Indonesian counterpart is served with peanut sauce.

Local Fruits

As both nations sit within the tropical zone, so many tropical fruits grow naturally within this region. Fruits such as mangoes, jackfruit, mangosteen, lychee, rambutan, star anise, bananas, and soursop are native to the area and are thus a huge part of the local culture and traditions.

Mangoes come in a variety of types across both the Philippines and Indonesia, and are typically eaten ripe. The sweetest mangoes are said to come from the Philippines, on the island of Guimaras. The carabao mango in particular is one of the most commonly grown mangoes in the Philippines, and its sweetness pairs it well with desserts. Both Tagalog and Bahasa Indonesia share the same word for mango, “mangga”. Some species such as white mango and patuhan mango are even grown in both countries.

Another major fruit crop, the banana, has hundreds of types in maritime Southeast Asia. Indonesia is one of the worlds largest producers of banana. The Philippines has its own variations of banana, with cavendish being the most commonly grown followed by saba and lakatan varieties. Fried bananas are enjoyed as a snack, as maruya is a local Filipino banana fritter and pisang goreng is an Indonesian is a local deep-fried banana.

Jackfruit is a more versatile fruit that is used in both savory and sweet dishes. The words for jackfruit, “langka” in Tagalog and “nangka” in Bahasa Indonesia are cognates of one another. The unripe fruit is used in savory dishes such as ginataang langka in the Philippines and gulai nangka in Indonesia. The ripe fruit can be eaten on its own, or used in desserts such as turon or halo-halo in the Philippines or in es campur and es teler in Indonesia.

Calamansi, a lime native to the Philippines, grows in parts of Indonesia, especially around north Sulawesi. It is used in local cuisines such as in kuah asam, a fish broth made with calamansi juice. Calamansi in the Philippines has a wider range of uses, from condiments to flavoring of dishes like sinigang and kinilaw. It is also a traditional ingredient in kesong puti, a local cheese made from carabao milk.

The use of fruits is also seen in the shaved ice desserts commonly eaten in the region. Halo-halo, one of the Philippines most popular desserts, blends shaved ice, grass jellies, ice cream, and fruits like macapuno, plantains and jackfruit, and fruit products like nata de coco58. In Indonesia, es campur uses a similar mix of ingredients, and is a popular dish to eat at iftar during Ramadan season. Another dessert, es teler, uses avocadoes, coconuts, and jackfruits alongside shaved ice and condensed milk.

The countries that make up the Malay Archipelago include Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei, Singapore, and Timor-Leste.

The Philippines has over 7,000 islands while Indonesia has over 17,000 islands.

National census results in 2020 showed a population of 109 million people in the Philippines and 270 million people in Indonesia.

This gesture is similar to hand-kissing found in the Middle East, and there’s even a similar tradition in Turkey where someone takes the persons hand and places it on their forehead. It might have spread via Muslim missionaries and traders and adopted by various peoples throughout maritime Southeast Asia.

In the Philippines, the barangay is the smallest administrative unit in the country. Barangay were traditionally coastal or river settlements.

Sari-sari stores are a huge part of tingi culture, where customers can buy units of a product rather than the whole package.

Ulam typically refers to any dish that is served alongside rice.

Both the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras and the Subak irrigation system are inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The water buffalo found in western Indonesia are not descended from Philippine carabao, instead come from a different population introduced through a separate route from mainland Southeast Asia.

Evidence of these large boats have been found in Butuan, Mindanao. These balangay boats that were uncovered date from the 10th to the 13th century, and are a testament to the advanced shipbuilding technology of maritime Southeast Asia. These boats helped facilitate trade, contact, and migration within Southeast Asia.

Another Austronesian ethnic group of Sea Nomads are the Orang Laut who live in western Indonesia around the Riau Archipelago, Malaysia, and around Singapore. Much like the Sama-Bajau, they live primarily on boats and in villages that are built above the water.

Tagalog is the basis of Filipino, the official language of the Philippines. While Filipino in theory takes on words from other local languages like Kapampangan, Cebuano, and Hiligaynon, a vast majority of its vocabulary stems from the Tagalog language.

Bahasa Indonesia is the official language of Indonesia, and derives from a dialect of Malay spoken in the Riau area. It is meant to act as a neutral language meant to unify the archipelago and its many ethnicities and islands. Bahasa Indonesia and Bahasa Melayu, the official language of Malaysia, are thus, very similar, and share many words in common.

Other Brahmic scripts in Southeast Asia include Old Kawi that was used to write the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, the oldest written record found in the Philippines that dates to the year 900, as well as Thai, Khmer, Lao, Cham, and Burmese scripts.

Today, the Jawi script is one of two official scripts in Brunei, and is used to write Bruneian Malay, particularly in signs and documents.

Salakot also goes by various names depending on language such as sarok in Visayan languages, Talugong in the Ivatan language, Saruk in the Yakan and Sama-Bajau language, and Hallidung in the Ifugao language.

Principalia were members of the aristocratic class during the Spanish colonial period, descended from pre-colonial datus who accepted Spanish rule and adopted Catholicism. The salakot they wore were made from prized materials like tortoiseshell and decorated with silver or gold.

The ancestral domain of the ethnic Malay people goes beyond current national borders. While heavily associated with the Malay Peninsula, they have historically lived in Riau, Kalimantan, and Sumatra in what is now modern day Indonesia.

Tapis in Lampung tradition in Sulawesi describes a wedding sarong for women.

The construction of the Barong Tagalog and the Baro’t Saya uses lightweight and often transparent materials, much like specific clothing styles in Indonesia such as specific kebaya varieties, the baju koko, and the baju bodo. The appearance of the baju bodo largely resembles what pre-colonial Tagalog and Visayan fashion looked like according to the Boxer Codex published in the late 1500s.

The Majapahit Empire existed from the 13th to the 16th century, and was the closest empire to unify maritime Southeast Asia. It was the last major Hindu-Buddhist empire in Indonesia before Islamic sultanates took hold and heralded the rise of Islam.

The palosebo came to the Philippines by way of Spanish colonial rule while pinjat pinang came to Indonesia through Dutch colonial rule.

Muslim Filipinos are collectively grouped under the term Moro, and share the Islamic religion as a common characteristic. The ethnic groups that fall under this term include the Maranao, Maguindanao, Tausug, Yakan, Iranun, and Jama Mapun.

Lumad is a collective term to describe indigenous peoples in Mindanao who historically have evaded Christianity and Islam and largely stuck to Animist tradition.

A notable difference in kulintang and gamelan ensembles is that kulintang ensembles feature a single row of gongs while gamelan typically feature double rows of gongs.

Examples of gong instruments being used in religious and spiritual settings include the ipat ritual of the Maguindanao people in the southern Philippines and the in holidays like Galungan, a Balinese holiday celebrating the victory of dharma over adharma.

Agung ensembles are also found among the peoples of Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysia and the Kalimantan region of Indonesia.

Variations of the word kacapi in Sulawesi include kacaping in Mandar, katapi for the Torajans , and simply kacapi for everyone from the central highland Kaili to the Kajang people.

Other local variations include the Rangku Alu of the Manggarai and the Magunatip of the Murut people on Borneo.

Igorot is a collective term to describe the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera Mounrains such as the Ifugao, Bontoc, Kalinga, and Apayao who have successfully resisted Spanish colonization and maintained much of their indigenous heritage.

The cultural significance of the banyan tree extends to India, as it is considered the national tree. In Hinduism, the lead of the banyan tree is the resting place of Krishna.

Banyan trees are also planted in the vicinity of main village temples in Bali.

In Balinese culture, a poleng cloth has a black and white square motif, and wrapped around places of worship in Bali. It symbolizes the concept of duality in Balinese Hinduism.

Indonesia has three floral emblems of national importance. White jasmine is the national flower, moon orchid is the flower of charm, and the rafflesia is the rare flower.

Traditional Javanese and Sundanese brides in their weddings use strings of jasmine garlands and are arranged as a hairnet to cover the bun. Other ethnic groups in Indonesia such as the Makassar and Bugis have a similar wedding tradition.

In canang sari offerings, white-colored flowers are pointed eastward as a symbol of Iswara.

Anito figures, or taotao, have been found in the island of Marinduque as well as in Katagalugan, or the ancestral homeland of the Tagalog people.

Galura is a winged assistant of Apung Sinukuan, represented as a giant eagle and believed to be the bringer of storms.

Tapai products that use desserts include peuyeum, a cassaca tapai, in Indonesia, and bibingka and puto in the Philippines.

Rice wines such as basi from Ilocos and tapuy of Banaue and Mountain Province in the Philippines come from tapai products.

In other local languages, glutinous rice is called pilit in Visayan and diket in Ilocano.

Kue is also referred to as Kuih in Malaysia and Singapore.

In Indonesia, kue can refer to other desserts and snacks not made with rice flour, such as martabak manis and pisang goreng.

Another dish that cooks glutinous rice in a bamboo tube is lemang, a Minangkabau rice dish that is cooked with coconut milk and salt. The insides have a banana leaf lining to prevent the rice from sticking to the bamboo. The Minahasan version is known as Nasi Jaha. In Pangasinan in the Philippines, binungey is a similar dish but without the use of banana leaf lining.

For the sake of brevity, the national language of both the Philippines and Indonesia will be referred to when speaking of these specific ingredients. Regional languages may have similar words, but there are simply too many languages to mention. Oftentimes, the use of putting the Tagalog and Indonesian word side-by-side is to show further similarities and to show that oftentimes, words in these languages are cognates of one another.

The word “asam” in Bahasa Indonesia is a cognate of the word “asim” in Tagalog, meaning sour. In this context, asam jawa means Javanese sour fruit.

Cabai rawit, also known as bird’s eye chili, is one of the most popular chilis in Southeast Asian cuisine, particularly in Thai, Indonesian, and Vietnamese cuisine.

There are at least 212 varieties of sambal, most of them from Java.

Sawsawan refers to dipping sauces served alongside dishes. A typical sawsawan is made by the diners personal preferences, and usually includes soy sauce, vinegar, patis, and chilis.

While a majority of local cuisines in the Philippines tends to be mild, the cuisine of peoples from Mindanao especially the Maranao are known for being spicy. Palapa is a frequent condiment used in Maranao cooking and adds spice to many local dishes.

The oldest Chinatown in the world is in Binondo, in Manila. Founded in 1594, the neighborhood was a place where Chinese settlers in what was then Spanish-era Philippines would’ve been allowed to live. In Jakarta, Glodok was established by the Dutch in 1740 as a district for ethnic Chinese.

Many of the most recognized brands and businesses in the Philippines today were established by Chinese-Filipinos, such as Jollibee, SM Supermalls, Mercury Drug, and Philippine Airlines.

A majority of Chinese diaspora populations in Southeast Asia primarily come from Hokkien communities, though there are also Hakka, Teochew, and Cantonese people who have settled in the region.

In Visayan regions, savory lugaw is known as pospas.

An interesting phenomenon in some Filipino dishes is that the name of the dishes may be Spanish, but its origins do not lie in Spain or its other former colonies. Arroz Caldo is one such example, as it is a localized version of Chinese-style porridge.

Another rice cake dish that derives from jian dui is Kapampangan moche in the Philippines, bearing a similar name to kue moci.

In other local languages, cincau is also referred to as kepleng in Javanese, camcauh in Sundanese, and daluman in Balinese.

Nata de coco was invented by Filipino food scientist Teódula Kalaw África, and this coconut jelly is used in many Filipino desserts. It was made to be an alternative to Nata de piña since the product was only available seasonally.

KUYA WHAT THE HECK!!!!!!!! THIS IS THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE pre-colonial writing I have ever consumed! Thank you so very much for writing this. I JUST CANNOT! WOW WOW WOW! Maraming salamat po. If people want to read up and research pre-colonial Philippines they need to start here!

Love this post, it’s so detailed, it’s clear there’s so much love for both cultures. Would love to make a post that goes deeper in the comparison of PH and Indonesian gong cultures, it’s really fun. Your piece was so inspiring!