We Need A Serious Re-framing When Discussing Filipino Culture

As an independent sovereign nation, we aren't just simply a former colony, and we should stop giving the colonizer so much credit.

The Philippines, a country in Southeast Asia that for many, is seen as an outlier of sorts. In a region full of Buddhists and Muslims, the country alongside Timor-Leste hosts a majority Catholic population. Spanish surnames are the most common surnames found throughout the country. Many historical sites here are churches and forts that date back to Spanish colonial rule. Christmas and Holy Week are one of the most important holidays in the country. Additionally, it was the sole U.S colony in Asia. Nowadays, one of main tourist draws to the country is that there isn’t a language barrier as a majority of the country can speak English, and this mentality is applied to jobs as well, since many Filipinos work as call-center agents in Manila where they primarily serve American clientele.

With all of these examples, it’s no wonder that when Filipinos or any outsiders discuss Filipino culture, they always start with how the Spanish and Americans colonized and influenced the culture, followed by a mention of Chinese and Malay influence. The Spanish and the Americans, and even the Chinese, get so much credit for the development of Filipino culture when it’s only really a part of the big picture.

My intention is not to erase the foreign influence, especially the colonial one. The influence of Spain and America will always be there, and it will always have a presence. It’s almost impossible to erase 300 years of colonial rule that made an archipelago majority Catholic, and another 50 or so years that made the archipelago quite proficient in English compared to most of Asia and develop a knack for basketball, fast food, malls, and American pop culture.

But what I think can be done is re-frame what the culture, or cultures of the nation is.

How To Properly Describe the Philippines and it’s Culture (or Cultures)

The best way to describe Filipino culture, in my opinion, is this:

It’s an Austronesian culture. Southeast Asian, but not too Indianized, nor too Sinicized. A former Spanish colony but not too Hispanicized. A former American colony but not too Americanized. Beneath a Westernized facade lies deep-seated Austronesian and Asian traditions that dictate how life is lived. Diverse in it’s 7,000 islands and it’s multi-ethnic composition, from highland cultures who carved the rice terraces to the seafarers who crafted ships that glide through the islands.

If we want to simplify this even further, we can say this:

Filipino culture is Austronesian and Southeast Asian, with some Chinese, Malay, Spanish, and American influence, as well as multi-ethnic and rooted in indigenous practices.

The following examples are, in my humble opinion, great ways to describe the culture, especially to those who may be unfamiliar with it. It recognizes the foreign and colonial elements but also puts the Austronesian and Southeast Asian elements to the forefront, where they belong. This isn’t to merely downplay the contributions of Spain and America to the country, but to instill a sense of pride in who the Filipino is without having to rely on the former colony. Instead of Spanish rule taking the front-and-center stage, it’s now a supporting role. It’s a way to de-center the West.

De-Centering the West When it Comes to History

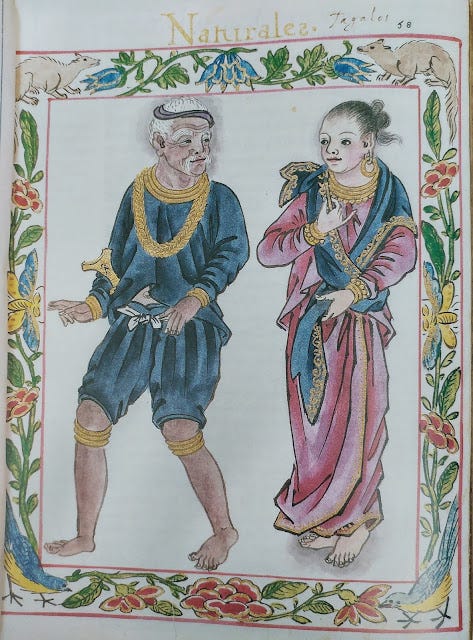

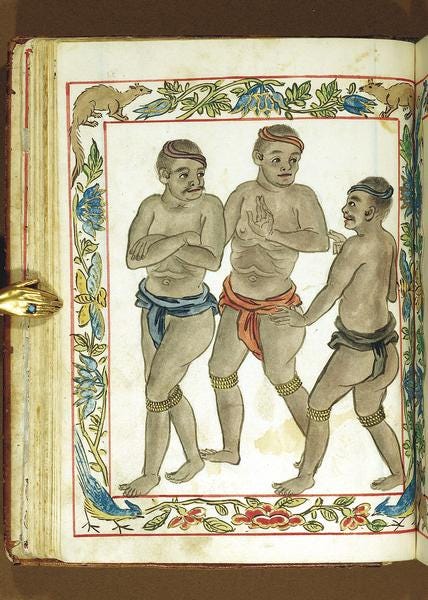

Another thing to discuss is how Filipino history is taught. The islands were not “discovered” in 1521, nor were they “civilized”. Manila isn’t just the former capitol of the Spanish East Indies. In fact, Manila’s history goes back further, with the earliest placename Tondo mentioned as early as the year 900. Tagalog culture developed on the Pasig River, and gave rise to the polities of Tondo, Maynila, and Namayan. Maynila was ruled by a paramount leader who took on the Malay title “Raja”. Although small, these polities wielded a good amount of influence, and had relations with China, Malacca, and Brunei. Trade Malay was the lingua franca during these ancient times.

Sultanates formed in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago with the introduction of Islam. The Sultanate of Sulu goes back to 1457. The Sultanate of Maguindanao was founded in 1515 by a preacher from Johore.

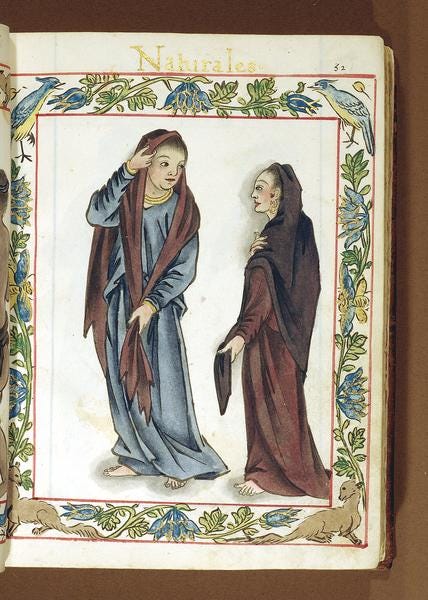

Another important facet of Filipino history that could be brought up more is that during Spanish, American, and even Japanese rule, Filipinos always fought back. Filipino history talks about the Battle of Mactan in 1521, Gomburza in 1872, the Philippine Revolution in 1898, as well as the writings of Jose Rizal, but how the colonial era can be taught is that resistance continued to happen and revolts and rebellions consistently popped up throughout the archipelago. Filipinos did not always accept colonial rule lying down flat, nor did they always openly accept the Catholic faith.

The Tamblot uprising in 1621-1622 in Bohol was a rebellion against Catholicism and the leader of the revolt, a babaylan, called for Boholanos to return to the old beliefs. That same year, the Bankaw revolt in Leyte got six towns to rise up in revolt, and in this revolt, a temple for a diwata was built. The Dagohoy rebellion in Bohol lasted from 1744 to 1825, and was started over matters of religious customs.

Rather than see the colonial period as a time when Filipinos just accepted it, this period of time was very much a period of continued resistance and rebellion.

Giving the Credit To Ourselves

One thing the many Filipinos do when discussing their culture is give most if not all the credit to a colonizer or some foreign power.

“Our churches were built by the Spanish.”

“We got noodles from the Chinese.”

“Our historical structures make us look like we are in Spain.”

And even some erroneous quotes like:

“The Spanish taught us how to make lechon.”

While it’s important to address that a certain cultural trait or a food item might originate from elsewhere, it’s also equally important to recognize that any aspect of culture adopted in a country will take on a local and indigenous form.

A good example is the bahay-na-bato. While some erroneously called it “Spanish architecture”, it is uniquely a Filipino-style home that was created during the Spanish colonial period. The style of home borrows influence from Spain, Mexico, China, as well as indigenous elements, so it’s a little unfair to credit this architectural style to only the Spanish. All these elements however, is what makes it Filipino. The construction of the house is ideal for the local climate. This is not a style of home that can be found in Spain.

The lower floor is typically made of stone, while the upper floor is made of wood, and where the primary residence lies. Windows are made of local capiz shell and slide open or shut. A Ventanilla allows for more air and light to enter a house. These houses were ultimately built as a response to the islands many natural disasters. They were built to withstand the many earthquakes and typhoons that hit the archipelago. And the most important detail, it was created for the Filipino lifestyle, even if it a style of home only the wealthy could afford to have. The bahay-na-bato is a Filipino style home created during the Spanish colonial era.

By extension, the historic city of Vigan, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is not simply an imitation of Spain. It is the the manifestation of how different cultures came to the region and interacted, fusing together to create an architectural style only found in the Philippines. To call the houses lining Calle Crisologo “Spanish-style” almost erases the mixing of cultures, the contributions of native Filipinos (Ilocanos in this specific case) that have helped to create these structures. Yes, the city followed a Spanish colonial city plan. It has a plaza flanked by an 18th-century cathedral, complete with a Western-style fountain. But all of its components, its history, the context, is what makes it Filipino.

To reference other colonial-era towns in Southeast Asia, Georgetown in Malaysia isn’t merely a “British town”, Kampot in Cambodia isn’t just built in the “French-style”, and nor is the old town of Batavia in Jakarta “just like being in the Netherlands.” The local people in these respective cities created a fusion style that uniquely belongs to them. Da Lat isn’t French, it’s Vietnamese. Singapore’s shophouses aren’t British, rather they are Peranakan. Vigan, much like these historic towns and buildings, take on a style different from their former colonial subjugators.

This kind of mentality even extends into food, and can lead to erroneous assumptions about Filipino food culture. For one, the introduction of Spanish loanwords into the many languages of the country has led some to believe for a long time that certain foods were introduced by the Spanish when that is simply not true.

Adobo isn’t a dish brought over by the Spaniards. It was actually a term used to describe a cooking method that already existed pre-colonization. Filipino adobo is vastly different to adobo in Latin America. Certain elements of what is now commonly known as adobo may have been influenced from the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade like the use of bay leaves, but the soul of adobo is indigenous.

Dishes like arroz caldo or lechon aren’t Spanish contributions. Arroz caldo is just a local version of rice porridge that was brought over by Chinese migrants, and of course, localized. Lechon, or the roasting of a whole pig, is also a food mislabeled as coming from Spain, simply because the name of the dish is rooted in Spanish, in Tagalog at least. Lemongrass, tamarind, citrus leaves, and binukaw are among the ingredients used in making and flavoring lechon. Visayan people called it inasal na baboy. This native dish which comes from the Austronesian cooking tradition of whole roasted pig simply took on a Spanish name. In fact, the closest dish to Filipino lechon is actually babi guling on the island of Bali in Indonesia.

While it’s accurate to say that food items like pancit and lumpia originally come from the Chinese, the fact that it has been localized makes it Filipino all on their own. Nasi goreng in Indonesia may have been brought over by Chinese migrants but it doesn’t make the dish any less Indonesian, in fact, it is considered one of five national dishes. Stir-fry noodle dishes like pad thai and pad see ew in Thailand, have roots in Chinese migrants but they are not any less Thai, in fact, like pancit in the Philippines, they are one of Thailand’s most recognized dishes.

And finally, another good example of localization is bread culture. While breadmaking did in fact come to the Philippines due to Spanish colonization and the opening of trade routes to the rest of the empire, the tradition of breadmaking took on a form of its own in the Philippines. Pan de sal is a uniquely Filipino tradition, and is associated with breakfast, and the bread sometimes uses dried-up malunggay leaves to be mixed in with the flour. Other local unique breads that are found in Filipino bakeries include pan de coco, monay, pan de siosa, pastel de Camiguin, and mamon. These bakery items are a unique aspect of the Filipino culinary tradition, and should be regarded in that way before the mention of Spanish influence comes up. To reference the culinary traditions of a neighboring country, the bread used in banh mi in Vietnam may originally come from French breadmaking traditions, but it is quintessentially a Vietnamese dish and takes on a form of its own, unique to the culture that created it.

I never thought lechon could be attributed to the Spanish.

In grade school, I read a book about a Chinese father and son who came home from toiling on the farm all day. They were distressed that their house was burning, and with it, the pig in the sty. The father accidentally touched the burnt pig and brought his fingers to his mouth to cool it. That's when he realized it was delicious, and lechon was born!

The stance here grabs attention. You call out the clutter, push for a hard reset on how we see things. The weight of old frames, the need to rethink stands out. This hits with bold clarity, dang!